| Image search results - "Princeps" |

Trajan: Augustus 98-117 AD Trajan ‘heroic bust’ AR Denarius

Denomination: AR Denarius

Year: Autumn 116-August 117 AD

Bust: Laureate ‘heroic’ bust right, wearing aegis, with bare chest showing

Obverse: IMP CAES NER TRAIAN OPTIM AVG GERM DAC

Reverse: PARTHICO P M TR P COS VI P P S P Q R

Type: Felicitas standing left, holding caduceus and cornucopiae

Mint: Rome

Weight & Measures: 3.41g; 19mm

RIC: RIC 333

Provenance: Ex Michael Kelly Collection of Roman Silver Coins; Ex CNG, E-sale 99, Lot 623 (10/13/2004).

Translation: OB: Imperator Caesar Nerva Trajan Optimus Princeps Augustus, Germanicus, Dacicus; for Emperor Caesar Nerva Trajan, The most perfect prince, Augustus, Conquerer of the Germans and Daicians.

Translation: Rev: Parthicus, Pontifex Maximus, Tribunicia Potestate, Consul VI, Pater Patriae, Senatus Populusque Romanus; for Conquer of the Parthians, High Priest, Tribune of the Roman people, Consul for the 6th time, Father of his country, as recognized by the senate and the people of Rome.

Notes: Felicitas, Roman goddess of good luck. Justin L1

|

|

(12) DOMITIAN81 - 96 AD

Struck as Caesar under Titus 80 AD

AR Denarius 18 mm 2.31 g

O: CAESAR DIVI F DOMITIANVS COS VII Laureate head right

R: PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Minerva advancing right with javelin and shield

Rome RCV 2674 laney

|

|

(12) DOMITIAN as Caesar81 - 96 AD

Struck as Caesar under Titus 80 AD

AR Denarius 18 mm 2.31 g

O: CAESAR DIVI F DOMITIANVS COS VII Laureate head right

R: PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Minerva advancing right with javelin and shield

Rome RCV 2674laney

|

|

0 Ric 1081 (Vespasian)Domitian Caesar 69-81

AR Denarius

Struck 79 AD

CAESAR AVG F DOMITIANVS COS VI

Laureate head right

PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS

Clasped hands before legionary eagle

3,13g/ 18mm

Ric 1081 (Vespasian)

Ex Tom VossenParthicus Maximus

|

|

00 Ric 266 (Titus)CAESAR DIVI F DOMITIANVS COS VII

laureate head right.

PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS

lighted & garlanded altar.

Domitian Caesar 69-81

AR Denarius

Struck 80-81

3,08g/19mm

Ric 266 (Titus)

Ex KünkerParthicus Maximus

|

|

013a6. DomitianAs Caesar under Titus. AR denarius. Obv: CAESAR DIVI F DOMITIANVS COS VII, laureate head right. Rev: PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, helmet on altar. RSC 399a, RIC 271[titus], Sear 2677.lawrence c

|

|

024a Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 1081, RIC II(1962) 0246D (Vespasian), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Clasped hands, #1024a Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 1081, RIC II(1962) 0246D (Vespasian), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Clasped hands, #1

avers:- CAESAR_AVG-F-DOMITIANVS-COS-VI, Laureate head of Domitian right.

revers:- PRINCEPS-IVVENTVTIS, Clasped hands holding a legionary eagle on prow.

exe: -/-//--, diameter: 18,5mm, weight: 3,18g, axis: 5h,

mint: Rome, date: 80 A.D., ref: RIC 1081, RIC II(1962) 0246D (Vespasian), RSC 393, BMC 269,

Q-001quadrans

|

|

024a Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 1084, RIC II(1962) 0243(Vespasian), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Salus standing right, Scarce!, #1024a Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 1084, RIC II(1962) 0243(Vespasian), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Salus standing right, Scarce!, #1

avers: CAESAR AVG F DOMITIANVS COS VI, Laureate head of Domitian right.

reverse: PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Salus standing right, leaning on column and feeding snake.

exergue: -/-//--, diameter: 17,0-18,0mm, weight: 3,17g, axis: 6h,

mint: Rome, date: 79 A.D., ref: RIC 1084, RIC II(1962) 0243(Vespasian) p-43, C 384, BMC 265,

Q-001quadrans

|

|

024a Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 1087, RIC II(1962) 0244(Vespasian), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Vesta seated left, Scarce!, #1024a Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 1087, RIC II(1962) 0244(Vespasian), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Vesta seated left, Scarce!, #1

avers: CAESAR AVG F DOMITIANVS COS VI, Laureate head of Domitian right.

reverse: PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Vesta seated left, holding palladium and sceptre.

exergue: -/-//--, diameter: 17,0-17,5mm, weight: 2,89g, axis: 6h,

mint: Rome, date: 79 A.D., ref: RIC 1087, RIC II(1962) 0244(Vespasian) p-43, C 378, BMC 262,

Q-001quadrans

|

|

024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0096, RIC II(1962) 0045(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Clasped hands, #1024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0096, RIC II(1962) 0045(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Clasped hands, #1

avers:- CAESAR_AVG-F-DOMITIANVS-COS-VII, Laureate head of Domitian right.

revers:- PRINCEPS-IVVENTVTIS, Clasped hands holding a legionary eagle on prow.

exe: -/-//--, diameter: 17,5mm, weight: 3,09g, axis: 5h,

mint: Rome, date: 80 A.D., ref: RIC 0096, RIC II(1962) 045(Titus) p-121, RSC 395, BMC 85,

Q-001quadrans

|

|

024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0266, RIC II(1962) 0050(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, lighted and garlanded altar, #1024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0266, RIC II(1962) 0050(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, lighted and garlanded altar, #1

avers:- CAESAR-DIVI-F-DOMITIANVS-COS-VII, Laureate head of Domitian right.

revers:- PRINCEPS-IVVENTVTIS, Lighted and garlanded altar.

exe: -/-//--, diameter: 17-18mm, weight: 2,93g, axis: 7h,

mint: Rome, date: 80 A.D., ref: RIC 0266, RIC II(1962) 0050(Titus) p-122, RSC 397a, BMC 92,

Q-001quadrans

|

|

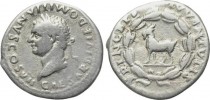

024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0267, RIC II(1962) 0049(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Cretan goat standing left, Scarce!, #1024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0267, RIC II(1962) 0049(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Cretan goat standing left, Scarce!, #1

avers:- CAESAR•DIVI-F-DOMITIANVS-COS-VII, Laureate head of Domitian right.

revers:- PRINCEPS-IVVENTVTIS, Cretan goat standing left within laurel wreath.

exe: -/-//--, diameter: mm, weight: g, axis: h,

mint: Rome, date: 80 A.D., ref: RIC 0267, RIC II(1962) 0049(Titus) p-122, RSC 390, BMC 88,

Q-001quadrans

|

|

024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0271, RIC II(1962) 0051(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Helmet on altar, #1024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0271, RIC II(1962) 0051(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Helmet on altar, #1

avers:- CAESAR-DIVI-F-DOMITIANVS-COS-VII, Laureate head of Domitian right.

revers:- PRINCEPS-IVVENTVTIS, Helmet on altar.

exe: -/-//--, diameter: 17,5-18mm, weight: 3,31g, axis: 5h,

mint: Rome, date: 80 A.D., ref: RIC 0271, RIC II(1962) 0051(Titus) p-122, RSC 399a, BMC 98,

Q-001quadrans

|

|

024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0271, RIC II(1962) 0051(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Helmet on altar, #2024b Domitian (69-81 A.D. Caesar, 81-96 A.D. Augustus), RIC 0271, RIC II(1962) 0051(Titus), AR-Denarius, Rome, PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Helmet on altar, #2

avers:- CAESAR-DIVI-F-DOMITIANVS-COS-VII, Laureate head of Domitian right.

revers:- PRINCEPS-IVVENTVTIS, Helmet on altar.

exe: -/-//--, diameter: 17,7-18,6mm, weight: 2,89g, axis: 5h,

mint: Rome, date: 80 A.D., ref: RIC 0271, RIC II(1962) 0051(Titus) p-122, RSC 399a, BMC 98,

Q-002quadrans

|

|

0261 - Denier tournois William II 1246-1278 ACObv/ Cross; around + G PRINCEPS.

Rev/ Castle; around, + CLARENTIA.

AG, 18.0 mm, 0.84 g

Mint: Clarentia (Achaia, Frankish Greece)

Metcalf/932

ex-Artemide Aste, auction 51E, lot 532dafnis

|

|

027 BC-14 AD - AUGUSTUS AR denarius - struck 2 BC-ca. 13 ADobv: CAESAR AVGVSTVS DIVI F PATER PATRIAE (laureate head right)

rev: AVGVSTI F COS DESIG PRINC IVVENT, C L CAESARES below (Gaius & Lucius standing front, each with a hand resting on a round shield, a spear, & in field above, a lituus right & simpulum left ["b9"])

ref: RIC I 207, BMC 533, RSC 43

mint: Lugdunum

3.35gms, 18mm

This type was struck to celebrate Gaius and Lucius Caesars, the sons of Marcus Agrippa, as heirs to the imperial throne. Gaius became Princeps Iuventutis in 5 BC and Lucius in 2 BC. They died in 4 AD and 2 AD respectively, thus promoting Tiberius to heir apparent. An obligatory issue for collectors.berserker

|

|

027 BC-14 AD - AVGVSTVS AE dupondius - struck by Cnaeus Piso Cn F moneyer (15 BC)obv: AVGVSTVS TRIBVNIC POTEST in wreath

rev: CN PISO CN IIIVIR A A A F F around large SC

ref: RIC I 381 (R), Cohen 378 (2frcs)

mint: Rome

10.33gms, 25mm

Rare

Augustus was awarded all the powers of the tribunate (tribunitia potestas) in addition to the governing authority of the consulate, cementing him as a supreme individual princeps, or emperor.berserker

|

|

035 - Domitian Denarius (as Caesar under Vespasian) - RIC II (Old) 244Obv:- CAESAR AVG F DOMITIANVS COS VI, Laureate head right

Rev:- PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS, Vesta seated left, holding Palladium and sceptre

Minted in Rome. A.D. 79

Reference:- RIC II (old) 244. RSC 378maridvnvm

|

|

1301a, Diocletian, 284-305 A.D. (Antioch)DIOCLETIAN (284 – 305 AD) AE Antoninianus, 293-95 AD, RIC V 322, Cohen 34. 20.70 mm/3.1 gm, aVF, Antioch. Obverse: IMP C C VAL DIOCLETIANVS P F AVG, Radiate bust right, draped & cuirassed; Reverse: CONCORDIA MILITVM, Jupiter presents Victory on a globe to Diocletian, I/XXI. Early Diocletian with dusty earthen green patina.

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Diocletian ( 284-305 A.D.)

Ralph W. Mathisen

University of South Carolina

Summary and Introduction

The Emperor Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus (A.D. 284-305) put an end to the disastrous phase of Roman history known as the "Military Anarchy" or the "Imperial Crisis" (235-284). He established an obvious military despotism and was responsible for laying the groundwork for the second phase of the Roman Empire, which is known variously as the "Dominate," the "Tetrarchy," the "Later Roman Empire," or the "Byzantine Empire." His reforms ensured the continuity of the Roman Empire in the east for more than a thousand years.

Diocletian's Early Life and Reign

Diocletian was born ca. 236/237 on the Dalmatian coast, perhaps at Salona. He was of very humble birth, and was originally named Diocles. He would have received little education beyond an elementary literacy and he was apparently deeply imbued with religious piety He had a wife Prisca and a daughter Valeria, both of whom reputedly were Christians. During Diocletian's early life, the Roman empire was in the midst of turmoil. In the early years of the third century, emperors increasingly insecure on their thrones had granted inflationary pay raises to the soldiers. The only meaningful income the soldiers now received was in the form of gold donatives granted by newly acclaimed emperors. Beginning in 235, armies throughout the empire began to set up their generals as rival emperors. The resultant civil wars opened up the empire to invasion in both the north, by the Franks, Alamanni, and Goths, and the east, by the Sassanid Persians. Another reason for the unrest in the army was the great gap between the social background of the common soldiers and the officer corps.

Diocletian sought his fortune in the army. He showed himself to be a shrewd, able, and ambitious individual. He is first attested as "Duke of Moesia" (an area on the banks of the lower Danube River), with responsibility for border defense. He was a prudent and methodical officer, a seeker of victory rather than glory. In 282, the legions of the upper Danube proclaimed the praetorian prefect Carus as emperor. Diocletian found favor under the new emperor, and was promoted to Count of the Domestics, the commander of the cavalry arm of the imperial bodyguard. In 283 he was granted the honor of a consulate.

In 284, in the midst of a campaign against the Persians, Carus was killed, struck by a bolt of lightning which one writer noted might have been forged in a legionary armory. This left the empire in the hands of his two young sons, Numerian in the east and Carinus in the west. Soon thereafter, Numerian died under mysterious circumstances near Nicomedia, and Diocletian was acclaimed emperor in his place. At this time he changed his name from Diocles to Diocletian. In 285 Carinus was killed in a battle near Belgrade, and Diocletian gained control of the entire empire.

Diocletian's Administrative and Military Reforms

As emperor, Diocletian was faced with many problems. His most immediate concerns were to bring the mutinous and increasingly barbarized Roman armies back under control and to make the frontiers once again secure from invasion. His long-term goals were to restore effective government and economic prosperity to the empire. Diocletian concluded that stern measures were necessary if these problems were to be solved. He felt that it was the responsibility of the imperial government to take whatever steps were necessary, no matter how harsh or innovative, to bring the empire back under control.

Diocletian was able to bring the army back under control by making several changes. He subdivided the roughly fifty existing provinces into approximately one hundred. The provinces also were apportioned among twelve "dioceses," each under a "vicar," and later also among four "prefectures," each under a "praetorian prefect." As a result, the imperial bureaucracy became increasingly bloated. He institutionalized the policy of separating civil and military careers. He divided the army itself into so-called "border troops," actually an ineffective citizen militia, and "palace troops," the real field army, which often was led by the emperor in person.

Following the precedent of Aurelian (A.D.270-275), Diocletian transformed the emperorship into an out-and-out oriental monarchy. Access to him became restricted; he now was addressed not as First Citizen (Princeps) or the soldierly general (Imperator), but as Lord and Master (Dominus Noster) . Those in audience were required to prostrate themselves on the ground before him.

Diocletian also concluded that the empire was too large and complex to be ruled by only a single emperor. Therefore, in order to provide an imperial presence throughout the empire, he introduced the "Tetrarchy," or "Rule by Four." In 285, he named his lieutenant Maximianus "Caesar," and assigned him the western half of the empire. This practice began the process which would culminate with the de facto split of the empire in 395. Both Diocletian and Maximianus adopted divine attributes. Diocletian was identified with Jupiter and Maximianus with Hercules. In 286, Diocletian promoted Maximianus to the rank of Augustus, "Senior Emperor," and in 293 he appointed two new Caesars, Constantius (the father of Constantine I ), who was given Gaul and Britain in the west, and Galerius, who was assigned the Balkans in the east.

By instituting his Tetrarchy, Diocletian also hoped to solve another problem. In the Augustan Principate, there had been no constitutional method for choosing new emperors. According to Diocletian's plan, the successor of each Augustus would be the respective Caesar, who then would name a new Caesar. Initially, the Tetrarchy operated smoothly and effectively.

Once the army was under control, Diocletian could turn his attention to other problems. The borders were restored and strengthened. In the early years of his reign, Diocletian and his subordinates were able to defeat foreign enemies such as Alamanni, Sarmatians, Saracens, Franks, and Persians, and to put down rebellions in Britain and Egypt. The easter frontier was actually expanded.

.

Diocletian's Economic Reforms

Another problem was the economy, which was in an especially sorry state. The coinage had become so debased as to be virtually worthless. Diocletian's attempt to reissue good gold and silver coins failed because there simply was not enough gold and silver available to restore confidence in the currency. A "Maximum Price Edict" issued in 301, intended to curb inflation, served only to drive goods onto the black market. Diocletian finally accepted the ruin of the money economy and revised the tax system so that it was based on payments in kind . The soldiers too came to be paid in kind.

In order to assure the long term survival of the empire, Diocletian identified certain occupations which he felt would have to be performed. These were known as the "compulsory services." They included such occupations as soldiers, bakers, members of town councils, and tenant farmers. These functions became hereditary, and those engaging in them were inhibited from changing their careers. The repetitious nature of these laws, however, suggests that they were not widely obeyed. Diocletian also expanded the policy of third-century emperors of restricting the entry of senators into high-ranking governmental posts, especially military ones.

Diocletian attempted to use the state religion as a unifying element. Encouraged by the Caesar Galerius, Diocletian in 303 issued a series of four increasingly harsh decrees designed to compel Christians to take part in the imperial cult, the traditional means by which allegiance was pledged to the empire. This began the so-called "Great Persecution."

Diocletian's Resignation and Death

On 1 May 305, wearied by his twenty years in office, and determined to implement his method for the imperial succession, Diocletian abdicated. He compelled his co-regent Maximianus to do the same. Constantius and Galerius then became the new Augusti, and two new Caesars were selected, Maximinus (305-313) in the east and Severus (305- 307) in the west. Diocletian then retired to his palace at Split on the Croatian coast. In 308 he declined an offer to resume the purple, and the aged ex-emperor died at Split on 3 December 316.

Copyright (C) 1996, Ralph W. Mathisen, University of South Carolina

Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

1301b, Diocletian, 20 November 284 - 1 March 305 A.D.Diocletian. RIC V Part II Cyzicus 256 var. Not listed with pellet in exegrue

Item ref: RI141f. VF. Minted in Cyzicus (B in centre field, XXI dot in exegrue)Obverse:- IMP CC VAL DIOCLETIANVS AVG, Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right. Reverse:- CONCORDIA MILITVM, Diocletian standing right, holding parazonium, receiving Victory from Jupiter standing left with scepter.

A post reform radiate of Diocletian. Ex Maridvnvm.

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Diocletian ( 284-305 A.D.)

Ralph W. Mathisen

University of South Carolina

Summary and Introduction

The Emperor Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus (A.D. 284-305) put an end to the disastrous phase of Roman history known as the "Military Anarchy" or the "Imperial Crisis" (235-284). He established an obvious military despotism and was responsible for laying the groundwork for the second phase of the Roman Empire, which is known variously as the "Dominate," the "Tetrarchy," the "Later Roman Empire," or the "Byzantine Empire." His reforms ensured the continuity of the Roman Empire in the east for more than a thousand years.

Diocletian's Early Life and Reign

Diocletian was born ca. 236/237 on the Dalmatian coast, perhaps at Salona. He was of very humble birth, and was originally named Diocles. He would have received little education beyond an elementary literacy and he was apparently deeply imbued with religious piety He had a wife Prisca and a daughter Valeria, both of whom reputedly were Christians. During Diocletian's early life, the Roman empire was in the midst of turmoil. In the early years of the third century, emperors increasingly insecure on their thrones had granted inflationary pay raises to the soldiers. The only meaningful income the soldiers now received was in the form of gold donatives granted by newly acclaimed emperors. Beginning in 235, armies throughout the empire began to set up their generals as rival emperors. The resultant civil wars opened up the empire to invasion in both the north, by the Franks, Alamanni, and Goths, and the east, by the Sassanid Persians. Another reason for the unrest in the army was the great gap between the social background of the common soldiers and the officer corps.

Diocletian sought his fortune in the army. He showed himself to be a shrewd, able, and ambitious individual. He is first attested as "Duke of Moesia" (an area on the banks of the lower Danube River), with responsibility for border defense. He was a prudent and methodical officer, a seeker of victory rather than glory. In 282, the legions of the upper Danube proclaimed the praetorian prefect Carus as emperor. Diocletian found favor under the new emperor, and was promoted to Count of the Domestics, the commander of the cavalry arm of the imperial bodyguard. In 283 he was granted the honor of a consulate.

In 284, in the midst of a campaign against the Persians, Carus was killed, struck by a bolt of lightning which one writer noted might have been forged in a legionary armory. This left the empire in the hands of his two young sons, Numerian in the east and Carinus in the west. Soon thereafter, Numerian died under mysterious circumstances near Nicomedia, and Diocletian was acclaimed emperor in his place. At this time he changed his name from Diocles to Diocletian. In 285 Carinus was killed in a battle near Belgrade, and Diocletian gained control of the entire empire.

Diocletian's Administrative and Military Reforms

As emperor, Diocletian was faced with many problems. His most immediate concerns were to bring the mutinous and increasingly barbarized Roman armies back under control and to make the frontiers once again secure from invasion. His long-term goals were to restore effective government and economic prosperity to the empire. Diocletian concluded that stern measures were necessary if these problems were to be solved. He felt that it was the responsibility of the imperial government to take whatever steps were necessary, no matter how harsh or innovative, to bring the empire back under control.

Diocletian was able to bring the army back under control by making several changes. He subdivided the roughly fifty existing provinces into approximately one hundred. The provinces also were apportioned among twelve "dioceses," each under a "vicar," and later also among four "prefectures," each under a "praetorian prefect." As a result, the imperial bureaucracy became increasingly bloated. He institutionalized the policy of separating civil and military careers. He divided the army itself into so-called "border troops," actually an ineffective citizen militia, and "palace troops," the real field army, which often was led by the emperor in person.

Following the precedent of Aurelian (A.D.270-275), Diocletian transformed the emperorship into an out-and-out oriental monarchy. Access to him became restricted; he now was addressed not as First Citizen (Princeps) or the soldierly general (Imperator), but as Lord and Master (Dominus Noster) . Those in audience were required to prostrate themselves on the ground before him.

Diocletian also concluded that the empire was too large and complex to be ruled by only a single emperor. Therefore, in order to provide an imperial presence throughout the empire, he introduced the "Tetrarchy," or "Rule by Four." In 285, he named his lieutenant Maximianus "Caesar," and assigned him the western half of the empire. This practice began the process which would culminate with the de facto split of the empire in 395. Both Diocletian and Maximianus adopted divine attributes. Diocletian was identified with Jupiter and Maximianus with Hercules. In 286, Diocletian promoted Maximianus to the rank of Augustus, "Senior Emperor," and in 293 he appointed two new Caesars, Constantius (the father of Constantine I ), who was given Gaul and Britain in the west, and Galerius, who was assigned the Balkans in the east.

By instituting his Tetrarchy, Diocletian also hoped to solve another problem. In the Augustan Principate, there had been no constitutional method for choosing new emperors. According to Diocletian's plan, the successor of each Augustus would be the respective Caesar, who then would name a new Caesar. Initially, the Tetrarchy operated smoothly and effectively.

Once the army was under control, Diocletian could turn his attention to other problems. The borders were restored and strengthened. In the early years of his reign, Diocletian and his subordinates were able to defeat foreign enemies such as Alamanni, Sarmatians, Saracens, Franks, and Persians, and to put down rebellions in Britain and Egypt. The easter frontier was actually expanded.

.

Diocletian's Economic Reforms

Another problem was the economy, which was in an especially sorry state. The coinage had become so debased as to be virtually worthless. Diocletian's attempt to reissue good gold and silver coins failed because there simply was not enough gold and silver available to restore confidence in the currency. A "Maximum Price Edict" issued in 301, intended to curb inflation, served only to drive goods onto the black market. Diocletian finally accepted the ruin of the money economy and revised the tax system so that it was based on payments in kind . The soldiers too came to be paid in kind.

In order to assure the long term survival of the empire, Diocletian identified certain occupations which he felt would have to be performed. These were known as the "compulsory services." They included such occupations as soldiers, bakers, members of town councils, and tenant farmers. These functions became hereditary, and those engaging in them were inhibited from changing their careers. The repetitious nature of these laws, however, suggests that they were not widely obeyed. Diocletian also expanded the policy of third-century emperors of restricting the entry of senators into high-ranking governmental posts, especially military ones.

Diocletian attempted to use the state religion as a unifying element. Encouraged by the Caesar Galerius, Diocletian in 303 issued a series of four increasingly harsh decrees designed to compel Christians to take part in the imperial cult, the traditional means by which allegiance was pledged to the empire. This began the so-called "Great Persecution."

Diocletian's Resignation and Death

On 1 May 305, wearied by his twenty years in office, and determined to implement his method for the imperial succession, Diocletian abdicated. He compelled his co-regent Maximianus to do the same. Constantius and Galerius then became the new Augusti, and two new Caesars were selected, Maximinus (305-313) in the east and Severus (305- 307) in the west. Diocletian then retired to his palace at Split on the Croatian coast. In 308 he declined an offer to resume the purple, and the aged ex-emperor died at Split on 3 December 316.

Copyright (C) 1996, Ralph W. Mathisen, University of South Carolina

Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

1307a, Maxentius, February 307 - 28 October 312 A.D.Bronze follis, RIC 163, aEF, Rome mint, 5.712g, 25.6mm, 0o, summer 307 A.D.; obverse MAXENTIVS P F AVG, laureate head right; reverse CONSERVATO-RES VRB SVAE, Roma holding globe and scepter, seated in hexastyle temple, RT in ex; rare. Ex FORVM; Ex Maridvnvm

De Imperatoribus Romanis : An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Maxentius (306-312 A.D.)

Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Salve Regina University

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius, more commonly known as Maxentius, was the child of the Emperor Maximianus Herculius and the Syrian, Eutropia; he was born ca. 278 A.D. After Galerius' appointment to the rank of Caesar on 1 March 293, Maxentius married Galerius' daughter Valeria Maximilla, who bore him a son named Romulus and another son whose name is unknown. Due to his haughty nature and bad disposition, Maxentius could seldom agree with his father or his father-in-law; Galerius' and Maximianus Herculius' aversion to Maxentius prevented the young man from becoming a Caesar in 305. Little else is known of Maxentius' private life prior to his accession and, although there is some evidence that it was spent in idleness, he did become a Senator.

On 28 October 306 Maxentius was acclaimed emperor, although he was politically astute enough not to use the title Augustus; like the Emperor Augustus, he called himself princeps. It was not until the summer of 307 that he started using the title Augustus and started offending other claimants to the imperial throne. He was enthroned by the plebs and the Praetorians. At the time of his acclamation Maxentius was at a public villa on the Via Labicana. He strengthened his position with promises of riches for those who helped him obtain his objective. He forced his father Maximianus Herculius to affirm his son's acclamation in order to give his regime a facade of legitimacy. His realm included Italy, Africa, Sardinia, and Corsica. As soon as Galerius learned about the acclamation of Herculius' son, he dispatched the Emperor Severus to quell the rebellion. With the help of his father and Severus' own troops, Maxentius' took his enemy prisoner.

When Severus died, Galerius was determined to avenge his death. In the early summer of 307 the Augustus invaded Italy; he advanced to the south and encamped at Interamna near the Tiber. His attempt to besiege the city was abortive because his army was not large enough to encompass the city's fortifications. Negotiations between Maxentius and Galerius broke down when the emperor discovered that the usurper was trying to win over his troops. Galerius' troops were open to Maxentius' promises because they were fighting a civil war between members of the same family; some of the soldiers went over to the enemy. Not trusting his own troops, Galerius withdrew. During its retreat, Galerius' army ravaged the Italian countryside as it was returning to its original base. If it was not enough that Maxentius had to deal with the havoc created by the ineffectual invasions of Severus and Galerius, he also had to deal with his father's attempts to regain the throne between 308 and 310. When Maximianus Herculius was unable to regain power by pushing his son off his throne, he attempted to win over Constantine to his cause. When this plan failed, he tried to win Diocletian over to his side at Carnuntum in October and November 308. Frustrated at every turn, Herculius returned to his son-in-law Constantine's side in Gaul where he died in 310, having been implicated in a plot against his son-in-law. Maxentius' control of the situation was weakened by the revolt of L. Domitius Alexander in 308. Although the revolt only lasted until the end of 309, it drastically cut the size of the grain supply availble for Rome. Maxentius' rule collapsed when he died on 27 October 312 in an engagement he had with the Emperor Constantine at the Milvian Bridge after the latter had invaded his realm.

Copyright (C) 1996, Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

1308b, Licinius I, 308 - 324 A.D. (Siscia)Licinius I, 11 November 308 - 18 September 324 A.D. Bronze follis, RIC 4, F, Siscia, 3.257g, 21.6mm, 0o, 313 - 315 A.D. Obverse: IMP LIC LICINIVS P F AVG, laureate head right; Reverse IOVI CONSERVATORI AVGG NN, Jupiter standing left holding Victory on globe and scepter, eagle with wreath in beak left, E right, SIS in exergue.

De Imperatoribus Romanis : An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Licinius (308-324 A.D.)

Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Salve Regina University

Licinius' Heritage

Valerius Licinianus Licinius, more commonly known as Licinius, may have been born ca. 265. Of peasant origin, his family was from Dacia. A close friend and comrade of arms of the Emperor Galerius, he accompanied him on his Persian expedition in 297. When campaigns by Severus and Galerius in late 306 or early 307 and in the summer of 307, respectively, failed to dislodge Maxentius who, with the luke warm support of his father Maximianus Herculius, was acclaimed princeps on 28 October 306, he was sent by the eastern emperor to Maxentius as an ambassador; the diplomatic mission, however, failed because the usurper refused to submit to the authority of his father-in-law Galerius. At the Conference of Carnuntum which was held in October or November of 308, Licinius was made an Augustus on 11 November 308; his realm included Thrace, Illyricum, and Pannonia.

Licinius' Early Reign

Although Licinius was initially appointed by Galerius to replace Severus to end the revolt of Maxentius , Licinius (perhaps wisely) made no effort to move against the usurper. In fact, his first attested victory was against the Sarmatians probably in the late spring, but no later than the end of June in 310. When the Emperor Galerius died in 311, Licinius met Maximinus Daia at the Bosporus during the early summer of that year; they concluded a treaty and divided Galerius' realm between them. It was little more than a year later that the Emperor Constantine defeated Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge on 28 October 312. After the defeat of the usurper, Constantine and Licinius met at Mediolanum (Milan) where Licinius married the former's sister Constantia; one child was born of this union: Valerius Licinianus Licinius. Licinius had another son, born of a slave woman, whose name is unknown. It appears that both emperors promulgated the so-called Edict of Milan, in which Constantine and Licinius granted Christians the freedom to practice their faith without any interference from the state.

As soon as he seems to have learned about the marital alliance between Licinius and Constantine and the death of Maxentius, who had been his ally, Daia traversed Asia Minor and, in April 313, he crossed the Bosporus and went to Byzantium, which he took from Licinius after an eleven day siege. On 30 April 313 the armies of both emperors clashed on the Campus Ergenus; in the ensuing battle Daia's forces were routed. A last ditch stand by Daia at the Cilician Gates failed; the eastern emperor subsequently died in the area of Tarsus probably in July or August 313. As soon as he arrived in Nicomedeia, Licinius promulgated the Edict of Milan. As soon as he had matters in Nicomedeia straightened out, Licinius campaigned against the Persians in the remaining part of 313 and the opening months of 314.

The First Civil War Between Licinius and Constantine

Once Licinius had defeated Maximinus Daia, the sole rulers of the Roman world were he and Constantine. It is obvious that the marriage of Licinius to Constantia was simply a union of convenience. In any case, there is evidence in the sources that both emperors were looking for an excuse to attack the other. The affair involving Bassianus (the husband of Constantius I's daughter Anastasia ), mentioned in the text of Anonymus Valesianus (5.14ff), may have sparked the falling out between the two emperors. In any case, Constantine' s forces joined battle with those of Licinius at Cibalae in Pannonia on 8 October 314. When the battle was over, Constantine prevailed; his victory, however, was Pyrrhic. Both emperors had been involved in exhausting military campaigns in the previous year and the months leading up to Cibalae and each of their realms had expanded so fast that their manpower reserves must have been stretched to the limit. Both men retreated to their own territory to lick their wounds. It may well be that the two emperors made an agreement, which has left no direct trace in the historical record, which would effectively restore the status quo.

Both emperors were variously engaged in different activities between 315 and 316. In addition to campaigning against the Germans while residing in Augusta Treverorum (Trier) in 315, Constantine dealt with aspects of the Donatist controversy; he also traveled to Rome where he celebrated his Decennalia. Licinius, possibly residing at Sirmium, was probably waging war against the Goths. Although not much else is known about Licinius' activities during this period, it is probable that he spent much of his time preparing for his impending war against Constantine; the latter,who spent the spring and summer of 316 in Augusta Treverorum, was probably doing much the same thing. In any case, by December 316, the western emperor was in Sardica with his army. Sometime between 1 December and 28 February 317, both emperors' armies joined battle on the Campus Ardiensis; as was the case in the previous engagement, Constantine' s forces were victorious. On 1 March 317, both sides agreed to a cessation of hostilities; possibly because of the intervention of his wife Constantia, Licinius was able to keep his throne, although he had to agree to the execution of his colleague Valens, who the eastern emperor had appointed as his colleague before the battle, as well as to cede some of his territory to his brother-in-law.

Licinius and the Christians

Although the historical record is not completely clear, Licinius seems to have campaigned against the Sarmatians in 318. He also appears to have been in Byzantium in the summer of 318 and later in June 323. Beyond these few facts, not much else is known about his residences until mid summer of 324. Although he and Constantine had issued the Edict of Milan in early 313, Licinius turned on the Christians in his realm seemingly in 320. The first law that Licinius issued prevented bishops from communicating with each other and from holding synods to discuss matters of interest to them. The second law prohibited men and women from attending services together and young girls from receiving instruction from their bishop or schools. When this law was issued, he also gave orders that Christians could hold services only outside of city walls. Additionally, he deprived officers in the army of their commissions if they did not sacrifice to the gods. Licinius may have been trying to incite Constantine to attack him. In any case, the growing tension between the two rulers is reflected in the consular Fasti of the period.

The Second Civil War Between Licinius and Constantine and Licinius' Death

War actually broke out in 321 when Constantine pursued some Sarmatians, who had been ravaging some territory in his realm, across the Danube. When he checked a similar invasion of the Goths, who were devastating Thrace, Licinius complained that Constantine had broken the treaty between them. Having assembled a fleet and army at Thessalonica, Constantine advanced toward Adrianople. Licinius engaged the forces of his brother-in-law near the banks of the Hebrus River on 3 July 324 where he was routed; with as many men as he could gather, he headed for his fleet which was in the Hellespont. Those of his soldiers who were not killed or put to flight, surrendered to the enemy. Licinius fled to Byzantium, where he was besieged by Constantine. Licinius' fleet, under the command of the admiral Abantus, was overcome by bad weather and by Constantine' s fleet which was under the command of his son Crispus. Hard pressed in Byzantium, Licinius abandoned the city to his rival and fled to Chalcedon in Bithynia. Leaving Martinianus, his former magister officiorum and now his co-ruler, to impede Constantine' s progress, Licinius regrouped his forces and engaged his enemy at Chrysopolis where he was again routed on 18 September 324. He fled to Nicomedeia which Constantine began to besiege. On the next day Licinius abdicated and was sent to Thessalonica, where he was kept under house arrest. Both Licinius and his associate were put to death by Constantine. Martinianus may have been put to death before the end of 324, whereas Licinius was not put to death until the spring of 325. Rumors circulated that Licinius had been put to death because he attempted another rebellion against Constantine.

Copyright (C) 1996, Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

1308c, Licinius I, 308-324 A.D. (Alexandria)Licinius I, 308-324 A.D. AE Follis, 3.60g, VF, 315 A.D., Alexandria. Obverse: IMP C VAL LICIN LICINIVS P F AVG - Laureate head right; Reverse: IOVI CONS-ERVATORI AVGG - Jupiter standing left, holding Victory on a globe and scepter; exergue: ALE / (wreath) over "B" over "N." Ref: RIC VII, 10 (B = r2) Rare, page 705 - Hunterian Museum, Glasgow, Scotland.

De Imperatoribus Romanis : An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Licinius (308-324 A.D.)

Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Salve Regina University

Licinius' Heritage

Valerius Licinianus Licinius, more commonly known as Licinius, may have been born ca. 265. Of peasant origin, his family was from Dacia. A close friend and comrade of arms of the Emperor Galerius, he accompanied him on his Persian expedition in 297. When campaigns by Severus and Galerius in late 306 or early 307 and in the summer of 307, respectively, failed to dislodge Maxentius who, with the luke warm support of his father Maximianus Herculius, was acclaimed princeps on 28 October 306, he was sent by the eastern emperor to Maxentius as an ambassador; the diplomatic mission, however, failed because the usurper refused to submit to the authority of his father-in-law Galerius. At the Conference of Carnuntum which was held in October or November of 308, Licinius was made an Augustus on 11 November 308; his realm included Thrace, Illyricum, and Pannonia.

Licinius' Early Reign

Although Licinius was initially appointed by Galerius to replace Severus to end the revolt of Maxentius , Licinius (perhaps wisely) made no effort to move against the usurper. In fact, his first attested victory was against the Sarmatians probably in the late spring, but no later than the end of June in 310. When the Emperor Galerius died in 311, Licinius met Maximinus Daia at the Bosporus during the early summer of that year; they concluded a treaty and divided Galerius' realm between them. It was little more than a year later that the Emperor Constantine defeated Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge on 28 October 312. After the defeat of the usurper, Constantine and Licinius met at Mediolanum (Milan) where Licinius married the former's sister Constantia; one child was born of this union: Valerius Licinianus Licinius. Licinius had another son, born of a slave woman, whose name is unknown. It appears that both emperors promulgated the so-called Edict of Milan, in which Constantine and Licinius granted Christians the freedom to practice their faith without any interference from the state.

As soon as he seems to have learned about the marital alliance between Licinius and Constantine and the death of Maxentius, who had been his ally, Daia traversed Asia Minor and, in April 313, he crossed the Bosporus and went to Byzantium, which he took from Licinius after an eleven day siege. On 30 April 313 the armies of both emperors clashed on the Campus Ergenus; in the ensuing battle Daia's forces were routed. A last ditch stand by Daia at the Cilician Gates failed; the eastern emperor subsequently died in the area of Tarsus probably in July or August 313. As soon as he arrived in Nicomedeia, Licinius promulgated the Edict of Milan. As soon as he had matters in Nicomedeia straightened out, Licinius campaigned against the Persians in the remaining part of 313 and the opening months of 314.

The First Civil War Between Licinius and Constantine

Once Licinius had defeated Maximinus Daia, the sole rulers of the Roman world were he and Constantine. It is obvious that the marriage of Licinius to Constantia was simply a union of convenience. In any case, there is evidence in the sources that both emperors were looking for an excuse to attack the other. The affair involving Bassianus (the husband of Constantius I's daughter Anastasia ), mentioned in the text of Anonymus Valesianus (5.14ff), may have sparked the falling out between the two emperors. In any case, Constantine' s forces joined battle with those of Licinius at Cibalae in Pannonia on 8 October 314. When the battle was over, Constantine prevailed; his victory, however, was Pyrrhic. Both emperors had been involved in exhausting military campaigns in the previous year and the months leading up to Cibalae and each of their realms had expanded so fast that their manpower reserves must have been stretched to the limit. Both men retreated to their own territory to lick their wounds. It may well be that the two emperors made an agreement, which has left no direct trace in the historical record, which would effectively restore the status quo.

Both emperors were variously engaged in different activities between 315 and 316. In addition to campaigning against the Germans while residing in Augusta Treverorum (Trier) in 315, Constantine dealt with aspects of the Donatist controversy; he also traveled to Rome where he celebrated his Decennalia. Licinius, possibly residing at Sirmium, was probably waging war against the Goths. Although not much else is known about Licinius' activities during this period, it is probable that he spent much of his time preparing for his impending war against Constantine; the latter,who spent the spring and summer of 316 in Augusta Treverorum, was probably doing much the same thing. In any case, by December 316, the western emperor was in Sardica with his army. Sometime between 1 December and 28 February 317, both emperors' armies joined battle on the Campus Ardiensis; as was the case in the previous engagement, Constantine' s forces were victorious. On 1 March 317, both sides agreed to a cessation of hostilities; possibly because of the intervention of his wife Constantia, Licinius was able to keep his throne, although he had to agree to the execution of his colleague Valens, who the eastern emperor had appointed as his colleague before the battle, as well as to cede some of his territory to his brother-in-law.

Licinius and the Christians

Although the historical record is not completely clear, Licinius seems to have campaigned against the Sarmatians in 318. He also appears to have been in Byzantium in the summer of 318 and later in June 323. Beyond these few facts, not much else is known about his residences until mid summer of 324. Although he and Constantine had issued the Edict of Milan in early 313, Licinius turned on the Christians in his realm seemingly in 320. The first law that Licinius issued prevented bishops from communicating with each other and from holding synods to discuss matters of interest to them. The second law prohibited men and women from attending services together and young girls from receiving instruction from their bishop or schools. When this law was issued, he also gave orders that Christians could hold services only outside of city walls. Additionally, he deprived officers in the army of their commissions if they did not sacrifice to the gods. Licinius may have been trying to incite Constantine to attack him. In any case, the growing tension between the two rulers is reflected in the consular Fasti of the period.

The Second Civil War Between Licinius and Constantine and Licinius' Death

War actually broke out in 321 when Constantine pursued some Sarmatians, who had been ravaging some territory in his realm, across the Danube. When he checked a similar invasion of the Goths, who were devastating Thrace, Licinius complained that Constantine had broken the treaty between them. Having assembled a fleet and army at Thessalonica, Constantine advanced toward Adrianople. Licinius engaged the forces of his brother-in-law near the banks of the Hebrus River on 3 July 324 where he was routed; with as many men as he could gather, he headed for his fleet which was in the Hellespont. Those of his soldiers who were not killed or put to flight, surrendered to the enemy. Licinius fled to Byzantium, where he was besieged by Constantine. Licinius' fleet, under the command of the admiral Abantus, was overcome by bad weather and by Constantine' s fleet which was under the command of his son Crispus. Hard pressed in Byzantium, Licinius abandoned the city to his rival and fled to Chalcedon in Bithynia. Leaving Martinianus, his former magister officiorum and now his co-ruler, to impede Constantine' s progress, Licinius regrouped his forces and engaged his enemy at Chrysopolis where he was again routed on 18 September 324. He fled to Nicomedeia which Constantine began to besiege. On the next day Licinius abdicated and was sent to Thessalonica, where he was kept under house arrest. Both Licinius and his associate were put to death by Constantine. Martinianus may have been put to death before the end of 324, whereas Licinius was not put to death until the spring of 325. Rumors circulated that Licinius had been put to death because he attempted another rebellion against Constantine.

Copyright (C) 1996, Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

14-37 AD - DRUSUS memorial AE As - struck under Tiberius (23 AD)obv: DRVSVS CAESAR TI AVG F DIVI AVG N (bare head left)

rev: PONTIF TRIBVN POTEST ITER around large S-C

ref: RIC I 45 (Tiberius), C.2 (2frcs)

10.14gms, 29mm

Drusus (also called Drusus Junior or Drusus the Younger), the only son of Tiberius, became heir to the throne after the death of Germanicus. One of his famous act connected to the mutiny in Pannonia, what broke out when the death of Augustus (19 August 14) was made known. Drusus left Rome to deal with the mutiny before the session of the Senate on the 17 September, when Tiberius was formally adopted him as princeps. He have reached the military camp in Pannonia in the time for the eclipse of the moon in the early hours of the 27 September wich so daunted the mutineers. He was also governor of Illyricum from 17 to 20 AD. Ancient sources concur that Livilla, his wife poisoned him. berserker

|

|

22116 Domitian/Vesta ReverseDomitian/Vesta struck under Vespasian 79 AD

Obv: CAESAR AVG F DOMITIANVS COS VI

Head of Domitian, laureate, right

Rev: PRINCEPS IVVENTVTIS

Vesta, draped, hooded, seated left on throne, holding palladium in ext right hand and transverse sceptre in left

Mint: Rome 17mm., 3,14g

RIC II, Part 1 (second edition) Vespasian 1087

Ex: Savoca Auction 16th Blue Auction

Blayne W

|

|

305b. Herennius EtruscusQuintus Herennius Etruscus Messius Decius (c. 227 - July 1, 251), was Roman emperor in 251, in a joint rule with his father Trajan Decius. Emperor Hostilian was his younger brother.

Herennius was born in Pannonia, during one of his father's military postings. His mother was Herennia Cupressenia Etruscilla, a Roman lady of an important senatorial family. Herennius was very close to his father and accompanied him in 248, as a military tribune, when Decius was appointed by Philip the Arab to deal with the revolt of Pacatianus in the Danube frontier. Decius was successful on defeating this usurper and felt confident to begin a rebellion of his own in the following year. Acclaimed emperor by his own troops, Decius marched into Italy and defeated Philip near modern Verona. In Rome, Herennius was declared heir to the throne and received the title of princeps iuventutis (prince of youth).

From the beginning of Herennius' accession, Gothic tribes raided across the Danube frontier and the provinces of Moesia and Dacia. At the beginning of 251, Decius elevated Herennius to the title of Augustus making him his co-emperor. Moreover, Herennius was chosen to be one of the year's consuls. The father and son, now joint rulers, then embarked in an expedition against king Cniva of the Goths to punish the invaders for the raids. Hostilian remained in Rome and the empress Herennia Etruscilla was named regent. Cniva and his men were returning to their lands with the booty, when the Roman army encountered them. Showing a very sophisticated military tactic, Cniva divided his army in smaller, more manageable groups and started to push back the Romans into a marshy swamp. On July 1, both armies engaged in the battle of Abrittus. Herennius died in battle, struck by an enemy arrow. Decius survived the initial confrontation, only to be slain with the rest of the army before the end of the day. Herennius and Decius were the first two emperors to be killed by a foreign army in battle.

With the news of the death of the emperors, the army proclaimed Trebonianus Gallus emperor, but in Rome they were succeeded by Hostilian, who would die shortly afterwards in an outbreak of plague.

Herennius Etruscus AR Antoninianus. Q HER ETR MES DECIVS NOB C, radiate draped bust right / CONCORDIA AVGG, clasped hands. RIC 138, RSC 4ecoli

|

|

305c. HostilianGaius Valens Hostilianus Messius Quintus (died 251), was Roman emperor in 251. Hostilian was born in an unknown date, after 230, as the son of the future emperor Trajan Decius by his wife Herennia Cupressenia Etruscilla. He was the younger brother of emperor Herennius Etruscus.

Following his father's accession to the throne, Hostilian received the treatment of an imperial prince, but was always kept in the shade of his brother Herennius, who enjoyed the privileges of being older and heir. In the beginning of 251, Decius elevated his son Herennius to co-emperor and Hostilian succeeded him in the title of princeps iuventutis (prince of youth). These dispositions were made previous to a campaign against king Cniva of the Goths, to punish him over the raids on the Danubian frontier. Hostilian remained in Rome due to his inexperience, and empress Herennia was named regent.

The campaign proved to be a disaster: both Herennius and Decius died in the Battle of Abrittus and became the first two emperors to be killed by a foreign army in battle. The armies in the Danube acclaimed Trebonianus Gallus emperor, but Rome acknowledged Hostilian's rights. Since Trebonianus was a respected general, there was fear of another civil war of succession, despite the fact that he chose to respect the will of Rome and adopted Hostilian. But later in 251, plague broke out in Rome and Hostilian died in the epidemic. He was the first emperor in 40 years and one of only 13 to die of natural causes. His timely death opened the way for the rule of Trebonianus with his natural son Volusianus.

Hostilian. Moesia Superior. Viminacium AE 25 mm. 11.7 g. Obverse: C VAL HOST M QVINTVS CAE. Draped bust right. Reverse: P M S COL VIM AN XII. Moesia standing left between lion and bull. ecoli

|

|

308. Valerian IRIC 209 Valerian I 253-260 AD AR Antoninianus of Moesia. Radiate draped bust/Aequitas standing holding balance and cornucopia.

Publius Licinius Valerianus (ca. 200-260), known in English as Valerian, was Roman emperor from 253 to 260. His full Latin title was IMPERATOR · CAESAR · PVBLIVS · LICINIVS · VALERIANVS · PIVS FELIX · INVICTVS · AVGVSTVS — in English, "Emperor Caesar Publius Licinus Valerianus Pious Lucky Undefeated Augustus."

Unlike the majority of the usurpers of the crisis of the third century, Valerian was of a noble and traditional Senatorial family. Details of his early life are elusive, but his marriage to Egnatia Mariniana who gave him two sons: Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus and Valerianus Minor is known.

In 238 he was princeps senatus, and Gordian I negotiated through him for Senatorial acknowledgement for his claim as Emperor. In 251, when Decius revived the censorship with legislative and executive powers so extensive that it practically embraced the civil authority of the Emperor, Valerian was chosen censor by the Senate. Under Decius he was nominated governor of the Rhine provinces of Noricum and Raetia and retained the confidence of his successor, Trebonianus Gallus, who asked him for reinforcements to quell the rebellion of Aemilianus in 253. Valerian headed south, but was too late: Gallus' own troops killed him and joined Aemilianus before his arrival. The Raetian soldiers then proclaimed Valerian emperor and continued their march towards Rome. At the time of his arrival in September, Aemilianus' legions defected, killing him and proclaiming Valerian emperor. In Rome, the Senate quickly acknowledged him, not only for fear of reprisals, but also because he was one of their own.

Valerian's first act as emperor was to make his son Gallienus colleague. In the beginning of his reign the affairs in Europe went from bad to worse and the whole West fell into disorder. In the East, Antioch had fallen into the hands of a Persian vassal, Armenia was occupied by Shapur I (Sapor). Valerian and Gallienus split the problems of the Empire between the two, with the son taking the West and the father heading East to face the Persian threat.

By 257, Valerian had already recovered Antioch and returned the Syrian province to Roman control but in the following year, the Goths ravaged Asia Minor. Later in 259, he moved to Edessa, but an outbreak of plague killed a critical number of legionaries, weakening the Roman position. Valerian was then forced to seek terms with Shapur I. Sometime towards the end of 259, or at the beginning of 260, Valerian was defeated and made prisoner by the Persians (making him the only Roman Emperor taken captive). It is said that he was subjected to the greatest insults by his captors, such as being used as a human stepladder by Shapur when mounting his horse. After his death in captivity, his skin was stuffed with straw and preserved as a trophy in the chief Persian temple. Only after Persian defeat in last Persia-Roman war three and a half centuries later was his skin destroyed.ecoli

|

|

313a. Tetricus IITetricus II was the son of Tetricus I and had exactly the same name as his father: C. Pius Esuvius Tetricus. His date of birth as well as the name of his mother are unknown. In 273 AD Tetricus II was elevated by his father to the rank of Caesar and given the title of princeps iuventutis. On 1 January 274 AD he entered in Augusta Treverorum (Trier) upon his first consulship, which he shared with his father.

After the defeat in autumn of 274 AD near Châlons-sur-Marne and subsequent surrender of his father Tetricus I to the emperor Aurelian, Tetricus II was put on display in Rome together with his father during Aurelian's triumph, but then pardoned. All literary sources agree on the fact that his life was spared; according to Aurelius Victor and the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, he even retained his senatorial rank and occupied later on many senatorial offices

Tet II obverse muled with his father's COMES AVG reverse.ecoli

|

|

408. MaxentiusMarcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius, more commonly known as Maxentius, was the child of the Emperor Maximianus Herculius and the Syrian Eutropia; he was born ca. 278 A.D. After Galerius' appointment to the rank of Caesar on 1 March 293, Maxentius married Galerius' daughter Valeria Maximilla, who bore him a son named Romulus and another son whose name is unknown. Due to his haughty nature and bad disposition, Maxentius could seldom agree with his father or his father-in-law; Galerius' and Maximianus Herculius' aversion to Maxentius prevented the young man from becoming a Caesar in 305. Little else is known of Maxentius' private life prior to his accession and, alth ough there is some evidence that it was spent in idleness, he did become a Senator.

On 28 October 306 Maxentius was acclaimed emperor, although he was politcally astute enough not to use the title Augustus; like the Emperor Augustus, he called himself princeps. It was not until the summer of 307 that he started usi ng the title Augustus and started offending other claimants to the imperial throne. He was enthroned by the plebs and the Praetorians. At the time of his acclamation Maxentius was at a public villa on the Via Labicana. He strengthened his position with promises of riches for those who helped him obtain his objective. He forced his father Maximianus Herculius to affirm his son's acclamation in order to give his regime a facade of legitimacy. His realm included Italy, Africa, Sardinia, and Corsica. As soon as Galerius learned about the acclamation of Herculius' son, he dispatched the Emperor Severus to quell the rebellion. With the help of his father and Severus' own troops, Maxentius' took his enemy prisoner.

When Severus died, Galerius was determined to avenge his death. In the early summer of 307 the Augustus invaded Italy; he advanced to the south and encamped at Interamna near the Tiber. His attempt to besiege the city was abortive because his army was not large enough to encompass the city's fortifications. Negotiations between Maxentius and Galerius broke down when the emperor discovered that the usurper was trying to win over his troops. Galerius' troops were open to Maxentius' promises because they were fighting a civil war between members of the same family; some of the soldiers went over to the enemy. Not trusting his own troops, Galerius withdrew. During its retreat, Galerius' army ravaged the Italian countryside as it was returning to its original base. If it was not enough that Maxentius had to deal with the havoc created by the ineffectual invasions of Severus and Galerius, he also had to deal with his father's attempts to regain the throne between 308 and 310. When Maximianus Herculius was unable to regain power by pushing his son off his throne, he attempted to win over Constantine to his cause. When this plan failed, he tried to win Diocletian over to his side at Carnuntum in October and November 308. Frustrated at every turn, Herculius returned to his son-in-law Constantine's side in Gaul where he died in 310, having been implicated in a plot against his son-in-law. Maxentius' control of the situation was weakened by the revolt of L. Domitius Alexander in 308. Although the revolt only lasted until the end of 309, it drastically cut the size of the grain supply availble for Rome. Maxentius' rule collapsed when he died on 27 October 312 in an engagement he had with the Emperor Constantine at the Milvian Bridge after the latter had invaded his realm.

Maxentius Follis. Ostia mint. IMP C MAXENTIVS P F AVG, laureate head right / AETE-RNITAS A-VGN, Castor and Pollux standing facing each other, each leaning on sceptre and holding bridled horse. ecoli

|

|

409. Maximinus II DazaCaius Valerius Galerius Maximinus, more commonly known as Maximinus Daia or Daza, was from Illyricum and was of peasant origin. He was born 20 November perhaps in the year 270. Daia was the son of Galerius' sister and had served in the army as a scutarius, Protector, and tribunus. He had been adopted by Galerius ; his name had been Daia even before that time. He had a wife and daughter, whose names are unknown, while his son's name was Maximus. When Diocletian and Maximianus Herculius resigned their posts of emperor on 1 May 305, they were succeeded by Constantius I Chlorus and Galerius as Augusti; their new Caesars were Severus and Maximinus Daia respectively. Constantius and Severus ruled in the West, whereas Galerius and Daia served in the East. Specifically, Daia's realm included the Middle East and the southern part of Asia Minor.[[1]]

Immediately after his appointment to the rank of Caesar, he went east and spent his first several years at Caesarea in Palestine. Events of the last quarter of 306 had a profound effect on the Emperor Galerius and his Caesar Daia. When Constantius I Chlorus died in July 306, the eastern emperor was forced by the course of events to accept Constantius' son Constantine as Caesar in the West; on 28 October of the same year, Maxentius , with the apparent backing of his father Maximianus Herculius, was acclaimed princeps. Both the attempt to dislodge Maxentius by Severus, who had been appointed Augustus of the West by Galerius after the death of Constantius in late 306 or early 307, and the subsequent campaign of Galerius himself in the summer of 307 failed. Because of the escalating nature of this chain of events, a Conference was called at Carnuntum in October and November 308; Licinius was appointed Augustus in Severus's place and Daia and Constantine were denoted filii Augustorum. Daia, however, unsatisfied with this sop tossed to him by Galerius, started calling himself Augustus in the spring of 310 when he seems to have campaigned against the Persians.[[2]] Although, as Caesar, he proved to be a trusted servant of Galerius until the latter died in 311, he subsequently seized the late emperor's domains. During the early summer of that year, he met with Licinius at the Bosporus; they concluded a treaty and divided Galerius' realm between them. Several yea rs later, after the death of Daia, Licinius obtained control of his domain. Like his mentor the late emperor, Daia had engaged in persecution of the Christians in his realm.[[3]]

In the autumn of 312, while Constantine was engaged against Maxentius, Daia appears to have been campaigning against the Armenians. In any case, he was back in Syria by February 313 when he seems to have learned about the marital alliance which had been forged by Constantine and Licinius. Disturbed by this course of events and the death of Maxentius, who had been his ally, Daia left Syria and reached Bythinia, although the harsh weather had seriously weakened his army. In April 313, he crossed the Bosporus and went to Byzantium, garrisoned by Licinius' troops; when the city refused to surrender, he took it after an eleven day siege. He moved to Heraclea, which he captured after a short siege; he then moved his forces to the first posting station. With only a small contingent of men, Licinius arrived at Adrianople while Daia was besieging Heraclea. On 30 April 313 the two armies clashed on the Campus Ergenus; in the ensuing battle Daia's forces were routed. Divesting himself of the purple and dressing like a slave, Daia fled to Nicomdeia. Subsequently, Daia attempted to stop the advance of Licinius at the Cilician Gates by establishing fortifications there; Licinius' army succeeded in breaking through, and Daia fled to Tarsus where he was hard pressed on land and sea. Daia died, probably in July or August 313, and was buried near Tarsus. Subsequently, the victorious emperor put Daia's wife and children to death.

Maximinus II Daza. 309-313 AD. ? Follis. Laureate head right / Genius standing left holding cornucopiae. ecoli

|

|

706a, Nero, 13 October 54 - 9 June 68 A.D.6, Nero, 13 October 54 - 9 June 68 A.D. AE setertius, Date: 66 AD; RIC I 516, 36.71 mm; 25.5 grams; aVF. Obverse: IMP NERO CAESAR AVG PONT MAX TR POT PP, Laureate bust right; Reverse: S C, ROMA, Roma seated left, exceptional portrait and full obverse legends. Ex Ancient Imports.

NERO (54-68 A.D.)

It is difficult for the modern student of history to realize just how popular Nero actually was, at least at the beginning of his reign. Rome looked upon her new Emperor with hope. He was the student of Seneca, and he had a sensitive nature. He loved art, music, literature, and theatre. He was also devoted to horses and horse racing—a devotion shared by many of his subjects. The plebs loved their new Emperor. As Professor of Classics Judith P. Hallett (University of Maryland, College Park) says, “It is not clear to me that Nero ever changed or that Nero ever grew-up, and that was both his strength and his weakness. Nero was an extraordinarily popular Emperor: he was like Elvis” (The Roman Empire in the First Century, III. Dir. Margaret Koval and Lyn Goldfarb. 2001. DVD. PBS/Warner Bros. 2003).

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Herbert W. Benario

Emory University

Introduction and Sources

The five Julio-Claudian emperors are very different one from the other. Augustus dominates in prestige and achievement from the enormous impact he had upon the Roman state and his long service to Rome, during which he attained unrivaled auctoritas. Tiberius was clearly the only possible successor when Augustus died in AD 14, but, upon his death twenty-three years later, the next three were a peculiar mix of viciousness, arrogance, and inexperience. Gaius, better known as Caligula, is generally styled a monster, whose brief tenure did Rome no service. His successor Claudius, his uncle, was a capable man who served Rome well, but was condemned for being subject to his wives and freedmen. The last of the dynasty, Nero, reigned more than three times as long as Gaius, and the damage for which he was responsible to the state was correspondingly greater. An emperor who is well described by statements such as these, "But above all he was carried away by a craze for popularity and he was jealous of all who in any way stirred the feeling of the mob." and "What an artist the world is losing!" and who is above all remembered for crimes against his mother and the Christians was indeed a sad falling-off from the levels of Augustus and Tiberius. Few will argue that Nero does not rank as one of the worst emperors of all.

The prime sources for Nero's life and reign are Tacitus' Annales 12-16, Suetonius' Life of Nero, and Dio Cassius' Roman History 61-63, written in the early third century. Additional valuable material comes from inscriptions, coinage, papyri, and archaeology.

Early Life

He was born on December 15, 37, at Antium, the son of Cnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbusand Agrippina. Domitius was a member of an ancient noble family, consul in 32; Agrippina was the daughter of the popular Germanicus, who had died in 19, and Agrippina, daughter of Agrippa, Augustus' closest associate, and Julia, the emperor's daughter, and thus in direct descent from the first princeps. When the child was born, his uncle Gaius had only recently become emperor. The relationship between mother and uncle was difficult, and Agrippina suffered occasional humiliation. But the family survived the short reign of the "crazy" emperor, and when he was assassinated, it chanced that Agrippina's uncle, Claudius, was the chosen of the praetorian guard, although there may have been a conspiracy to accomplish this.

Ahenobarbus had died in 40, so the son was now the responsibility of Agrippina alone. She lived as a private citizen for much of the decade, until the death of Messalina, the emperor's wife, in 48 made competition among several likely candidates to become the new empress inevitable. Although Roman law forbade marriage between uncle and niece, an eloquent speech in the senate by Lucius Vitellius, Claudius' closest advisor in the senatorial order, persuaded his audience that the public good required their union. The marriage took place in 49, and soon thereafter the philosopher Seneca [[PIR2 A617]] was recalled from exile to become the young Domitius' tutor, a relationship which endured for some dozen years.

His advance was thereafter rapid. He was adopted by Claudius the following year and took the name Tiberius Claudius Nero Caesar or Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus, was preferred to Claudius' natural son, Britannicus, who was about three years younger, was betrothed to the emperor's daughter Octavia, and was, in the eyes of the people, the clear successor to the emperor. In 54, Claudius died, having eaten some poisoned mushrooms, responsibility for which was believed to be Agrippina's, and the young Nero, not yet seventeen years old, was hailed on October 13 as emperor by the praetorian guard.

The First Years of Rule

The first five years of Nero's rule are customarily called the quinquennium, a period of good government under the influence, not always coinciding, of three people, his mother, Seneca, and Sextus Afranius Burrus, the praetorian prefect. The latter two were allies in their "education" of the emperor. Seneca continued his philosophical and rhetorical training, Burrus was more involved in advising on the actualities of government. They often combined their influence against Agrippina, who, having made her son emperor, never let him forget the debt he owed his mother, until finally, and fatally, he moved against her.

Nero's betrothal to Octavia was a significant step in his ultimate accession to the throne, as it were, but she was too quiet, too shy, too modest for his taste. He was early attracted to Poppaea Sabina, the wife of Otho, and she continually goaded him to break from Octavia and to show himself an adult by opposing his mother. In his private life, Nero honed the musical and artistic tastes which were his chief interest, but, at this stage, they were kept private, at the instigation of Seneca and Burrus.

As the year 59 began, Nero had just celebrated his twenty-first birthday and now felt the need to employ the powers which he possessed as emperor as he wished, without the limits imposed by others. Poppaea's urgings had their effect, first of all, at the very onset of the year, with Nero's murder of his mother in the Bay of Naples.

Agrippina had tried desperately to retain her influence with her son, going so far as to have intercourse with him. But the break between them proved irrevocable, and Nero undertook various devices to eliminate his mother without the appearance of guilt on his part. The choice was a splendid vessel which would collapse while she was on board. As this happened, she swam ashore and, when her attendant, having cried out that she was Agrippina, was clubbed to death, Agrippina knew what was going on. She sent Nero a message that she was well; his response was to send a detachment of sailors to finish the job. When she was struck across the head, she bared her womb and said, "Strike here, Anicetus, strike here, for this bore Nero," and she was brutally murdered.

Nero was petrified with fear when he learned that the deed had been done, yet his popularity with the plebs of Rome was not impaired. This matricide, however, proved a turning point in his life and principate. It appeared that all shackles were now removed. The influence of Seneca and Burrus began to wane, and when Burrus died in 62, Seneca realized that his powers of persuasion were at an end and soon went into retirement. Britannicus had died as early as 55; now Octavia was to follow, and Nero became free to marry Poppaea. It may be that it had been Burrus rather than Agrippina who had continually urged that Nero's position depended in large part upon his marriage to Octavia. Burrus' successor as commander of the praetorian guard, although now with a colleague, was Ofonius Tigellinus, quite the opposite of Burrus in character and outlook. Tigellinus became Nero's "evil twin," urging and assisting in the performance of crimes and the satisfaction of lusts.

Administrative and Foreign Policy

With Seneca and Burrus in charge of administration at home, the first half-dozen years of Nero's principate ran smoothly. He himself devoted his attention to his artistic, literary, and physical bents, with music, poetry, and chariot racing to the fore. But his advisors were able to keep these performances and displays private, with small, select audiences on hand. Yet there was a gradual trend toward public performance, with the establishment of games. Further, he spent many nights roaming the city in disguise, with numerous companions, who terrorized the streets and attacked individuals. Those who dared to defend themselves often faced death afterward, because they had shown disrespect for the emperor. The die was being cast for the last phases of Nero's reign.

The Great Fire at Rome and The Punishment

of the Christians

The year 64 was the most significant of Nero's principate up to this point. His mother and wife were dead, as was Burrus, and Seneca, unable to maintain his influence over Nero without his colleague's support, had withdrawn into private life. The abysmal Tigellinus was now the foremost advisor of the still young emperor, a man whose origin was from the lowest levels of society and who can accurately be described as criminal in outlook and action. Yet Nero must have considered that he was happier than he had ever been in his life. Those who had constrained his enjoyment of his (seemingly) limitless power were gone, he was married to Poppaea, a woman with all advantages save for a bad character the empire was essentially at peace, and the people of Rome enjoyed a full measure of panem et circenses. But then occurred one of the greatest disasters that the city of Rome, in its long history, had ever endured.

The fire began in the southeastern angle of the Circus Maximus, spreading through the shops which clustered there, and raged for the better part of a week. There was brief success in controlling the blaze, but then it burst forth once more, so that many people claimed that the fires were deliberately set. After about a fortnight, the fire burned itself out, having consumed ten of the fourteen Augustan regions into which the city had been divided.