| Image search results - "PERSIAN" |

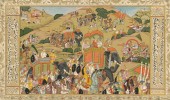

Indian Mughal, original miniature painting with illuminated borders painted on the reverse of an unrelated original 18th Century Persian manuscript with mentions of Mahadev (Shiva), Parvati, daughter of Himalaya and Byas. The folio script is about Byas begot Singh and Singh upbringing, suggesting Persian Abd al-Rahman Chishtis at Al-makhlukat (1631-32), which includes Islamic and Sanskrit sacred Parana - Ramayana and Mahabharata (Persian - Razm-nama) - the story of creation.Quant.Geek

|

|

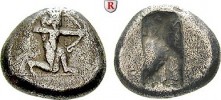

Persian Empire, Lydia, Anatolia, Xerxes I - Darius II, c. 485 - 420 B.C. Silver siglos, Carradice Type IIIa variety without pellets, Carradice NC 1998, pl. 8, 5 - 16; or underweight Carradice IIIb, Choice gVF, attractive surfaces, flow lines, bankers mark on edge, Sardes (Sart, Turkey) mint, weight 5.403g, maximum diameter 14.8mm, c. 485 - 420 B.C.; obverse kneeling-running figure of the Great King right, transverse spear downward in right hand, bow in extended left hand, bearded, crowned; reverse irregular rectangular punch; from the CEB Collection; ex Numismatic Fine Arts winter sale (Dec 1987), lot 371

Ex: Forum Ancient Coins.

Persian Lydia, Persian Empire, Lydia, Anatolia, Xerxes I - Darius II, c. 485 - 420 B.C., Carradice Type III was initially issued with the same weight standard as earlier sigloi, Type IIIa, c. 5.30 - 5.39 g. Carradice NC 1998 lists 12 examples of sigloi in the Type IIIa style but without pellets behind the beard. There may have been two mints, one issuing with the two pellets and one without. Or possibly all light weight examples without pellets are simply underweight examples of the Type IIIb, issued after c. 485 B.C. on a heavier standard, c. 5.55 - 5.60 g.paul1888

|

|

Time of Alexander I, AR Hemiobol, struck 470 - 460 BC at Argilos in MacedoniaObverse: No legend. Forepart of Pegasos facing left.

Reverse: No legend. Quadripartite granulated incuse square.

Diameter: 8.78mm | Weight: 0.20gms | Die Axis: Uncertain

Liampi 118 | SNG - | GCV -

Rare

Argilos was a city of ancient Macedonia founded by a colony of Greeks from Andros. Although little information is known about the city until about 480 BC, the literary tradition dates the foundation to around 655/654 BC which makes Argilos the earliest Greek colony on the Thracian coast. It appears from Herodotus to have been a little to the right of the route the army of Xerxes I took during its invasion of Greece in 480 BC in the Greco-Persian Wars. Its territory must have extended as far as the right bank of the Strymona, since the mountain of Kerdylion belonged to the city.

Argilos benefited from the trading activities along the Strymona and probably also from the gold mines of the Pangeion. Ancient authors rarely mention the site, but nevertheless shed some light on the important periods of its history. In the last quarter of the 6th century BC, Argilos founded two colonies, Tragilos, in the Thracian heartland, and Kerdilion, a few kilometers to the east of the city.

Alexander I was the ruler of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from c.498 BC until his death in 454 BC. Alexander came to the throne during the era of the kingdom's vassalage to Persia, dating back to the time of his father, Amyntas I. Although Macedonia retained a broad scope of autonomy, in 492 BC it was made a fully subordinate part of the Persian Empire. Alexander I acted as a representative of the Persian governor Mardonius during peace negotiations after the Persian defeat at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC. From the time of Mardonius' conquest of Macedonia, Herodotus disparagingly refers to Alexander I as “hyparchos”, meaning viceroy. However, despite his cooperation with Persia, Alexander frequently gave supplies and advice to the Greek city states, and warned them of the Persian plans before the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC. After their defeat at Plataea, when the Persian army under the command of Artabazus tried to retreat all the way back to Asia Minor, most of the 43,000 survivors of the battle were attacked and killed by the forces of Alexander at the estuary of the Strymona river.

Alexander regained Macedonian independence after the end of the Persian Wars and was given the title "philhellene" by the Athenians, a title used for Greek patriots.

After the Persian defeat, Argilos became a member of the first Athenian confederation but the foundation of Amphipolis in 437 BC, which took control of the trade along the Strymona, brought an end to this. Thucydides tells us that some Argilians took part in this foundation but that the relations between the two cities quickly deteriorated and, during the Peloponnesian war, the Argilians joined with the Spartan general Brasidas to attack Amphipolis. An inscription from the temple of Asklepios in Epidauros attests that Argilos was an independent city during the 4th century.

Like other colonies in the area, Argilos was conquered by the Macedonian king Philip II in 357 B.C. Historians believe that the city was then abandoned and, though excavations have brought to light an important agricultural settlement on the acropolis dated to the years 350-200 BC, no Roman or Byzantine ruins have been uncovered there.*Alex

|

|

JUSTINIAN I, AE Follis (40 Nummi), struck 529 - 533 at Antioch (Theoupolis)Obverse: D N IVSTINIANVS P P AVG. Justinian enthroned facing, holding long sceptre in his right hand and globus cruciger in his left.

Reverse: Large M, cross above and officina letter (Δ = 4th Officina) below, asterisk in field to left of M and outward facing crescent in field to right; in exergue, +THEUP

Diameter: 34mm | Weight: 18.69gms | Die Axis: 5

SBCV: 214 | DOC: 206d.1

Much of Antioch was destroyed by a great earthquake on 29th November 528 and, following this disaster, the city was renamed Theoupolis.

530: In the spring of this year Belisarius and Hermogenes (magister officiorum) defeated a combined Persian-Arab army of 50,000 men at the Battle of Dara in modern Turkey, and in the summer a Byzantine cavalry force under the command of Sittas defeated a major Persian invasion into Roman Armenia at the Battle of Satala.

531: On April 19th, at the Battle of Callinicum, a Byzantine army commanded by Belisarius, was defeated by the Persians at Raqqa in northern Syria. Nevertheless, Justinian negotiated an end to the hostilities and Belisarius was hailed as a hero.

532: On January 11th this year anger among the supporters of the most important chariot teams in Constantinople, the Blues and the Greens, escalated into violence towards the emperor. For the next five days the city was in chaos and the fires that started during the rioting resulted in the destruction of much of the city. This insurrection, known as the Nika riots, was put down a week later by Belisarius and Mundus resulting in 30,000 people being killed in the Hippodrome.

On February 23rd Justinian ordered the building of a new Christian basilica in Constantinople, the Hagia Sophia. More than 10,000 people were employed in the construction using material brought from all over the empire.

*Alex

|

|

JUSTINIAN I, AE Half-Follis (20 Nummi), struck 527 – 528 at AntiochObverse: D N IVSTINIANVS P P AVG. Diademed, draped and cuirassed bust of Justinian I facing right.

Reverse: Large K, Large latin cross to left dividing letters A–N / T–X; officina letter to right of K (Γ = third officina).

Diameter: 28mm | Weight: 5.8gms | Die Axis: 12

SBCV: 224a | Not in DOC

Rare

This coin was struck prior to Antioch being renamed Theoupolis following the great earthquake that virtually destroyed the city on 29th November 528.

527: One of Justinian's first acts as sole emperor was to reorganise the command structure of the Byzantine army. He appointed Belisarius to command the Eastern army in Armenia and on the Byzantine-Persian frontier.

528: In February of this year Justinian appointed a commission to codify all the laws of the Roman Empire that were still in force from Hadrian to the current date. This Code of Civil Laws came to be called the Codex Justinianus.

On November 29th a great earthquake struck Antioch, killing thousands and destroying much of the city including the Domus Aurea (Great Church) built by Constantine the Great.*Alex

|

|

JUSTINIAN I, AE Half-Follis (20 Nummi), struck 529 – 533 at Antioch (Theoupolis)Obverse: D N IVSTINIANVS P P AVG. Justinian I enthroned facing, holding long sceptre in his right hand and globus cruciger in his left.

Reverse: Large K, Large latin cross to left dividing letters T–H/Є–U/O/P; officina letter to right of K (Δ = fourth officina).

Diameter: 28mm | Weight: 8.4gms | Die Axis: 11

SBCV: 225 | DOC: 208.6

Rare

Much of Antioch was destroyed by a great earthquake on 29th November 528 and, following this disaster, the city was renamed Theoupolis.

530: In the spring of this year Belisarius and Hermogenes (magister officiorum) defeated a combined Persian-Arab army of 50,000 men at the Battle of Dara in modern Turkey, and in the summer a Byzantine cavalry force under the command of Sittas defeated a major Persian invasion into Roman Armenia at the Battle of Satala.

531: On April 19th, at the Battle of Callinicum, a Byzantine army commanded by Belisarius, was defeated by the Persians at Raqqa in northern Syria. Nevertheless, Justinian negotiated an end to the hostilities and Belisarius was hailed as a hero.

532: On January 11th this year anger among the supporters of the most important chariot teams in Constantinople, the Blues and the Greens, escalated into violence towards the emperor. For the next five days the city was in chaos and the fires that started during the rioting resulted in the destruction of much of the city. This insurrection, known as the Nika riots, was put down a week later by Belisarius and Mundus resulting in 30,000 people being killed in the Hippodrome.

On February 23rd Justinian ordered the building of a new Christian basilica in Constantinople, the Hagia Sophia. More than 10,000 people were employed in the construction using material brought from all over the empire.

*Alex

|

|

Philip II, 359 - 336 BC. AE18. Struck after 356 BC at an uncertain mint in MacedoniaObverse: No legend. Young male head, usually identified as Apollo, with hair bound in a taenia, facing left.

Reverse: ΦIΛIΠΠOY, Naked rider on horse prancing left, uncertain control mark, often described as the head of a lion, beneath the horse. The control mark looks a bit like the ram on the prow of a galley to me, but that is just my personal opinion.

Diameter: 17.4mm | Weight: 6.9gms | Die Axis: 12

SNG ANS 872 - 874

The bronze series of this type is extensive and differentiated principally by the different control marks. These control marks are symbols and letters which generally appear on the reverse, very occasionally the obverse, of the coin, and they were used to identify the officials responsible for a particular issue of coinage.

Philip II won the horseback race at the 106th Olympics in 356 BC, and it is thought that the horseman on the reverse of this coin commemorates that event.

Philip II of Macedon was King of Macedon from 359 until his death in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III Arrhidaeus. In 357 BC, Philip married Olympias, who was the daughter of the king of the Molossians. Alexander was born in 356 BC, the same year as Philip's horse won at the Olympic Games.

Only Greeks were allowed to participate in the Olympic Games, and Philip was determined to convince his Athenian opposition that he was indeed worthy to be considered Greek. And, after successfully uniting Macedonia and Thessaly, Philip could legitimately participate in the Olympics. In 365 BC Philip entered his horse into the keles, a horseback race in the 106th Olympics, and won. He proceeded to win two more times, winning the four horse chariot race in the 352 BC 107th Olympics and the two horse chariot race in the 348 BC 108th Olympics. These were great victories for Philip because not only had he been admitted officially into the Olympic Games but he had also won, solidifying his standing as a true Greek.

The conquest and political consolidation of most of Greece during Philip's reign was achieved in part by the creation of the Macedonian phalanx which gave him an enormous advantage on the battlefield. After defeating Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC Philip II established the League of Corinth, a federation of Greek states, with him at it's head, with the intention of invading the Persian empire. In 336 BC he sent an army of 10,000 men into Asia Minor to make preparations for the invasion by freeing the Greeks living on the western coast and islands from Persian rule. All went well until the news arrived that Philip had been assassinated. The Macedonians were demoralized by Philip's death and were subsequently defeated by Persian forces near Magnesia.

Philip II was murdered in October 336 BC, at Aegae, the ancient capital of the Macedonian kingdom, while he was entering into the town's theatre. He was assassinated by Pausanius, one of his own bodyguards, who was himself slain by three of Philip's other bodyguards. The reasons for Philip's assassination are not now fully known, with many modern historians saying that, on the face of it, none of the ancient accounts which have come down to us appear to be credible.*Alex

|

|

Philip II, 359 - 336 BC. AE18. Struck after 356 BC at an uncertain mint in MacedoniaObverse: No legend. Young male head, usually identified as Apollo, with hair bound in a taenia, facing left.

Reverse: ΦIΛIΠΠOY, Naked rider on horse prancing right, forepart of bull butting right control mark (helmet?) beneath the horse.

Diameter: 19mm | Weight: 6.95gms | Die Axis: 9

GCV: 6699 | Forrer/Weber: 2068

The bronze series of this type is extensive and differentiated principally by the different control marks. These control marks are symbols and letters which generally appear on the reverse, very occasionally the obverse, of the coin, and they were used to identify the officials responsible for a particular issue of coinage.

Philip II won the horseback race at the 106th Olympics in 356 BC, and it is thought that the horseman on the reverse of this coin commemorates this event.

Philip II of Macedon was King of Macedon from 359 until his death in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III Arrhidaeus. In 357 BC, Philip married Olympias, who was the daughter of the king of the Molossians. Alexander was born in 356 BC, the same year as Philip's horse won at the Olympic Games.

The conquest and political consolidation of most of Greece during Philip's reign was achieved in part by the creation of the Macedonian phalanx which gave him an enormous advantage on the battlefield. After defeating Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC Philip II established the League of Corinth, a federation of Greek states, with him at it's head, with the intention of invading the Persian empire. In 336 BC, Philip II sent an army of 10,000 men into Asia Minor to make preparations for the invasion by freeing the Greeks living on the western coast and islands from Persian rule. All went well until the news arrived that Philip had been assassinated. The Macedonians were demoralized by Philip's death and were subsequently defeated by Persian forces near Magnesia.

Philip II was murdered in October 336 BC, at Aegae, the ancient capital of the Macedonian kingdom, while he was entering into the town's theatre. He was assassinated by Pausanius, one of his own bodyguards, who was himself slain by three of Philip's other bodyguards. The reasons for Philip's assassination are not now fully known, with many modern historians saying that, on the face of it, none of the ancient accounts which have come down to us appear to be credible.*Alex

|

|

Philip II, 359 - 336. AE18. Struck after 356 BC at an uncertain mint in Macedonia Obverse: No legend. Young male head, usually identified as Apollo, with hair bound in a taenia, facing right.

Reverse: ΦIΛIΠΠOY, Naked rider on horse prancing right, retrograde E control mark beneath the horse.

Diameter: 17.16mm | Weight: 6.09gms | Die Axis: 12

SNG ANS 919 - 920

The bronze series of this type is extensive and differentiated principally by the different control marks. These control marks are symbols and letters which generally appear on the reverse, very occasionally the obverse, of the coin, and they were used to identify the officials responsible for a particular issue of coinage.

Philip II won the horseback race at the 106th Olympics in 356 BC, and it is thought that the horseman on the reverse of this coin commemorates this event.

Philip II of Macedon was King of Macedon from 359 until his death in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III Arrhidaeus. In 357 BC, Philip married Olympias, who was the daughter of the king of the Molossians. Alexander was born in 356 BC, the same year as Philip's horse won at the Olympic Games.

The conquest and political consolidation of most of Greece during Philip's reign was achieved in part by the creation of the Macedonian phalanx which gave him an enormous advantage on the battlefield. After defeating Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC Philip II established the League of Corinth, a federation of Greek states, with him at it's head, with the intention of invading the Persian empire. In 336 BC, Philip II sent an army of 10,000 men into Asia Minor to make preparations for the invasion by freeing the Greeks living on the western coast and islands from Persian rule. All went well until the news arrived that Philip had been assassinated. The Macedonians were demoralized by Philip's death and were subsequently defeated by Persian forces near Magnesia.

Philip II was murdered in October 336 BC, at Aegae, the ancient capital of the Macedonian kingdom, while he was entering into the town's theatre. He was assassinated by Pausanius, one of his own bodyguards, who was himself slain by three of Philip's other bodyguards. The reasons for Philip's assassination are not now fully known, with many modern historians saying that, on the face of it, none of the ancient accounts which have come down to us appear to be credible.*Alex

|

|

Philip II, 359 - 336. AE18. Struck after 356 BC at an uncertain mint in MacedoniaObverse: No legend. Young male head, usually identified as Apollo, with hair bound in a taenia, facing right.

Reverse: ΦIΛIΠΠOY, Naked rider on horse prancing left, spearhead control mark beneath the horse.

Diameter: 18.00mm | Weight: 6.00gms | Die Axis: 12

SNG ANS 850 | Mionnet I: 750

The bronze series of this type is extensive and differentiated principally by the different control marks. These control marks are symbols and letters which generally appear on the reverse, very occasionally the obverse, of the coin, and they were used to identify the officials responsible for a particular issue of coinage.

Philip II won the horseback race at the 106th Olympics in 356 BC, and it is thought that the horseman on the reverse of this coin commemorates this event.

Philip II of Macedon was King of Macedon from 359 until his death in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III Arrhidaeus. In 357 BC, Philip married Olympias, who was the daughter of the king of the Molossians. Alexander was born in 356 BC, the same year as Philip's horse won at the Olympic Games.

The conquest and political consolidation of most of Greece during Philip's reign was achieved in part by the creation of the Macedonian phalanx which gave him an enormous advantage on the battlefield. After defeating Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC Philip II established the League of Corinth, a federation of Greek states, with him at it's head, with the intention of invading the Persian empire. In 336 BC, Philip II sent an army of 10,000 men into Asia Minor to make preparations for the invasion by freeing the Greeks living on the western coast and islands from Persian rule. All went well until the news arrived that Philip had been assassinated. The Macedonians were demoralized by Philip's death and were subsequently defeated by Persian forces near Magnesia.

Philip II was murdered in October 336 BC, at Aegae, the ancient capital of the Macedonian kingdom, while he was entering into the town's theatre. He was assassinated by Pausanius, one of his own bodyguards, who was himself slain by three of Philip's other bodyguards. The reasons for Philip's assassination are not now fully known, with many modern historians saying that, on the face of it, none of the ancient accounts which have come down to us appear to be credible.*Alex

|

|

Philip III Arrhidaios, 323 - 317 BC. Bronze Tetartemorion (Dichalkon / Quarter Obol). Struck 323 - 315 BC under Nikokreon at Salamis, Cyprus.Obverse: No legend. Macedonian shield with Gorgoneion (Medusa) head as the boss in the centre. The shield boss is sometimes called the episema, the Greek name for a symbol of a particular city or clan which was placed in the centre of a soldier's shield.

Reverse: Macedonian helmet surmounted with a horse hair crest; B - A (for BAΣIΛEOΣ AΛEΞANΔPOY = King Alexander) above; mint marks below the helmet, to left, a kerykeion (caduceus) and to the right, the monogram NK (for Nikokreon).

Diameter: 14mm | Weight: 4.6gms | Die Axis: 1

Price: 3162 | Liampi, Chronologie 170-92

This coin is a Type 7 (Macedonian shield type) bronze Quarter-Obol (two chalkoi). Price dated the Macedonian Shield coins as beginning during the latter part of Alexander's life, c.325 BC, and ending c.310 BC. Liampi later argued, based on new hoard evidence, that they were minted as early as 334 BC. This particular coin is dated from c.323 to 315 BC during the reign of Philip III Arrhidaios.

Salamis was founded around 1100 BC by the inhabitants of Enkomi, a Late Bronze Age city on Cyprus, though in Homeric tradition, the city was established by Teucer, one of the Greek princes who fought in the Trojan War. After Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, of which Salamis was a part, Greek culture and art flourished in the city and, as well as being the seat of the governor of Cyprus, it was the island's most important port.

Nikokreon had succeeded Pnytagoras on the throne of Salamis and is reported to have paid homage to Alexander after the conqueror's return from Egypt to Tyre in 331 BC. After Alexander's death, his empire was split between his generals, Cyprus falling to Ptolomy I of Egypt. In 315 BC during the war between Antigonos and Ptolemy, Nikokreon supported the latter and was rewarded by being made governor of all Cyprus. However, in 311 BC Ptolemy forced Nikokreon to commit suicide because he no longer trusted him. Ptolemy's brother, King Menelaus, was made governor in Nikokreon's stead.

In 306 BC, Salamis was the scene of a naval battle between the fleets of Ptolemy and Demetrius I of Macedon. Demetrius won the battle and captured the island. *Alex

|

|

MUGHALS-AURANGZEB-SURAT-MINT-AH-1095-RY-27-ONE-RUPEE-Abu'l Muzaffar Muhi-ud-Din Muhammad (3 November 1618 – 3 March 1707), commonly known as Aurangzeb or by his regnal title Alamgir (Persian: "Conqueror of the World"), was the sixth, and widely considered the last effective Mughal emperor. His reign lasted for 49 years from 1658 until his death in 1707. _1200Antonivs Protti

|

|

Xerxes IIAchaemenid Empire. Time of Darios I to Xerxes II, circa 485-420 BC. Siglos (Silver, 16 mm, 5.38 g), Sardes. Persian king or hero in kneeling/running stance to right, holding spear and bow. Rev. Incuse punch. Carradice Type IIIa/b. Beautifully toned. Very fine.arash p

|

|

0001 Sasanian Empire Khusro II -- Year 2 -- BishapurObv: Pahlavi script legend: to the l. on two lines reading down leftward and outward is GDH/'pzwt (xwarrah abzūd) and to the r. on one line reading down is hwslwd (Husraw) = Khusro has increased the royal glory; frontal bust facing r. of bearded Khusro II with a hair globe drawn to the back of the neck, crown with three merlons and attached to the top of the crown cap are wings (group of pellets within the base) with an attached crescent and star, double pearl diadem with three ribbons behind, earring made up of three dots, neckline edged with a row of pearls, both shoulders decorated with a crescent and star, double row of pearls from shoulders to breast, two dots on the breast, star in upper l. field, star and crescent in upper r. field, two dotted rims with a star on a crescent at 3h, 6h, and 9h.

Rev: Pahlavi script legend: to the l. reading down is year tlyn of Khusro II's reign and to the r. reading down is the mint mark BYSh = year 2 of Khusro II's reign, Bishapur; fire altar with a base consisting of two slabs and a shaft with two ribbons pointing upwards to the r. and l. of the shaft with four altar slabs on top and flames consisting of four tiers rendered as four then three then two then one upward stroke, star to the l. and crescent to the r. of the top two tiers, to the l. and r. of the altar are two frontal facing attendants each holding a sword pointing downwards with the r. hand over the l. hand and wearing a rounded cap, three dotted rims with a star on a crescent at 3h, 6h, 9h, and 12h.

Denomination: silver drachm; Mint: Bishapur; Date: year 2, 591 - 592 AD; Weight: 4.12g; Diameter: 29mm; Die axis: 90º; References, for example: Göbl II/2; SNS Iran 580 and 581 (same mint and regnal year).

Regnal year 2 saw major changes to the coinage of Khusro II. First, the defeat of Wahrām Chōbēn (Wahrām VI) brought to an end the interruption of Khusro II's xwarrah and so wings representing Vərəθraγna/Verethragna (Avestan), Wahrām (Middle Persian), Bahrām (Persian), i.e. the god or personification of victory, were added to Khusro II's crown. Second, for the first time in Sasanian coinage the ideogram GDH (xwarrah) is added to the legend (obverse). Third, on the reverse six pointed stars are added to the crescent moons outside of the three dotted rims at 3h, 6h, 9h, and 12h. Six pointed stars can be considered representations of the sun (see Gariboldi 2010 pp. 36ff and the sources referenced in footnote 71, p. 37).

See Daryaee (1997) for an interesting study of the religious and political iconography on the coinage of Khusro II*. He argues that Khusro II implemented iconographic changes in regnal year 2 (591 - 592 AD) as a direct result of suppressing the rebellion (with the assistance of the Byzantine Emperor Maurice) of the brilliant general Wahrām Chōbēn (Wahrām VI) in 591 AD. Further iconographic changes were carried out in regnal year 11 (600 - 601 AD) in response to the final defeat in 600 AD of the 10 year rule/rebellion of Wistahm**, his uncle (as the brother-in-law of his father Ohrmazd IV) and former staunch supporter.

*The study cannot be intended to be complete. For example, there is no discussion of the legend 'pd that appeared, beginning in the 12th regnal year but not present for all subsequent years or at all mints, in the second quadrant outside of the rims on the obverse. Gariboldi 2010 (p.64) translates the legend as "good", "excellent", "wonderful" while Göbl 1983 (p. 331) translates it as "praise".

**There is some debate about when Wistahm was finally eliminated. Daryaee, following Paruck 1924, relies on (purported?) numismatic evidence that the last coin minted in his name was for year 10. Therefore Daryaee states that 600 AD was the year of elimination (Daryaee 1997, p. 53 n. 38. Also see Daryaee 2009, p. 33 n. 166 for a slightly more tepid assertion). Frye 1984 implies a 10 year rule for Wistahm, stating that "it was not until 601 that the rule of Chosroes [Khusro] was restored over all of the empire..." (p. 336). Göbl SN, however, states that 10 years of reign are said to be represented, although personally he had only seen coins of years 2 through 7 (p. 53). Thus Wistahm's years in SN's Table XI are listed as "591/2 - 597?" Malek 1993 also lists Wistahm's years as 591/2 - 97 (p. 237).

Provenance: Ex Stephen Album Rare Coins Auction 36, January 25, 2020

Photo Credit: Stephen Album Rare Coins

Sources

Daryaee, Touraj. 'The Use of Religio-Political Propaganda on Coins of Xusrō II." The Journal of the American Numismatics (1989-), vol. 9 (1997): 41-53.

Daryaee, Touraj. Sasanian Persia: The Rise And Fall Of An Empire. London: I. B. Tauris, 2009.

Frye, Richard. The History of Ancient Iran. Munich: C.H. Beck’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1984.

Gariboldi, Andrea. Sasanian Coinage and History: The Civic Numismatic Collection of Milan. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 2010.

Göbl, Robert. Sasanian Numismatics. Braunschweig: Klinkhardt and Biermann, 1971.

Göbl 1983: Yarshater, Ehsan, ed. The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 3 (1), The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983: 322 - 336.

Malek, Hodge. "A Survey of Research on Sasanian Numismatics." The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-), vol. 153 (1993): 227 - 269.

Paruck, F.D.J. Sasanian Coins. Bombay: 1924.

SNS Iran: Akbarzadeh, Daryoosh and Nikolaus Schindel. Sylloge Nummorum Sasanidarum Iran A Late Sasanian Hoard from Orumiyeh. Wien: Österreichischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften, 2017.

Tracy Aiello

|

|

0006 Rider and Larissa SeatedThessaly Greece, the City of Larissa

Obv: Rider on a horse prancing r. on groundline, holding a single spear transversally with petasos flying backwards and chlamys on his back, beneath horse's belly a lion's head facing r. Border of dots or small grains.1

Rev: The nymph Larissa2 seated r. on a chair with a back ending in a swan's head, r. hand resting on her lap or thigh and holding a phiale, l. arm raised with palm forward,3 Λ and Α above to l. and r. of head with R and Ι to r. of body turned 90º and downward, all within a shallow incuse square.

Denomination: silver trihemiobol; Mint: Larissa; Date: mid- to late 5th Century BC4; Weight: 1.28g5; Diameter: 13mm; Die axis: 60º; References, for example: BMC Thessaly p. 25, 13; Warren 687 var. No mention of lion's head; Weber 2838; Traité IV, 651, pl. CCXCVI, 9; Herrmann Group II, pl. I, 7; Boston MFA 875 var. no lion's head and reference to two spears; Lorber 2008 pl. 41, 5; BCD Thessaly II 154; HGC 4, 466.

Notes:

1Forrer, BCD Thessaly II, and Hoover refer to the border as composed of dots; Babelon refers to the border as composed of small grains.

2Herrmann does not associate the figure on the reverse with the nymph Larissa. Instead he refers to the figure as a "sitting male" and cites two examples from Berlin and Warren 687 as having the indication of beards (p.9). He declares that the meaning [interpretation] of the sitter cannot be determined, but he invites us to think of a deity (p. 11). Brett in Boston MFA follows Herrmann's interpretation.

3Forrer and BCD Thessaly II state that Larissa is holding a mirror, Hoover mentions only that the arm is raised, Babelon indicates that the left arm is raised with palm forward, and Herrmann describes the left hand as raised in an "adoring gesture". On the coin here the left hand clearly has the thumb separated from the rest of the fingers with the palm facing forward; there is no indication that the hand is holding anything. I wonder what the intention of the gesture could have been.

4Dates in the sources cited here run the gamut of the 5th Century BC. Herrmann: c. 500 - 479 BC; Babelon: c. 470 - 430 BC; HGC: c. 440 - 420 BC; Forrer: c. 430 - 400 BC. In light of Kagen (2004) and his belief that Herrmann's Group I ended c. 460 BC it seems appropriate to choose the date range specified in BCD Thessaly II.

5Herrmann argues that Group II was struck on the Persian weight standard. (He believed that the same held true for Group I). Kagan (2004) demonstrates that Larissain coinage was not struck on the Persian weight standard.

The city of Larissa was named after the local water nymph, said to be the daughter of Pelasgos. He was said to be the ancestor of the pre-Greek Pelasgians. According to myth Larissa drowned while playing ball on the banks of the Peneios river. (HGC 4 p. 130).

Provenance: Ex Nomos AG December 8, 2019.

Photo Credits: Nomos AG

CLICK FOR SOURCESTracy Aiello

|

|

002a, Aigina, Islands off Attica, Greece, c. 510 - 490 B.C.Silver stater, S 1849, SNG Cop 503, F, 12.231g, 22.3mm, Aigina (Aegina) mint, c. 510 - 490 B.C.; Obverse: sea turtle (with row of dots down the middle); Reverse: incuse square of “Union Jack” pattern; banker's mark obverse. Ex FORVM.

Greek Turtles, by Gary T. Anderson

Turtles, the archaic currency of Aegina, are among the most sought after of all ancient coins. Their early history is somewhat of a mystery. At one time historians debated whether they or the issuances of Lydia were the world's earliest coins. The source of this idea comes indirectly from the writings of Heracleides of Pontus, a fourth century BC Greek scholar. In the treatise Etymologicum, Orion quotes Heracleides as claiming that King Pheidon of Argos, who died no later than 650 BC, was the first to strike coins at Aegina. However, archeological investigations date the earliest turtles to about 550 BC, and historians now believe that this is when the first of these intriguing coins were stamped.

Aegina is a small, mountainous island in the Saronikon Gulf, about midway between Attica and the Peloponnese. In the sixth century BC it was perhaps the foremost of the Greek maritime powers, with trade routes throughout the eastern half of the Mediterranean. It is through contacts with Greeks in Asia Minor that the idea of coinage was probably introduced to Aegina. Either the Lydians or Greeks along the coast of present day Turkey were most likely the first to produce coins, back in the late seventh century. These consisted of lumps of a metal called electrum (a mixture of gold and silver) stamped with an official impression to guarantee the coin was of a certain weight. Aegina picked up on this idea and improved upon it by stamping coins of (relatively) pure silver instead electrum, which contained varying proportions of gold and silver. The image stamped on the coin of the mighty sea power was that of a sea turtle, an animal that was plentiful in the Aegean Sea. While rival cities of Athens and Corinth would soon begin limited manufacture of coins, it is the turtle that became the dominant currency of southern Greece. The reason for this is the shear number of coins produced, estimated to be ten thousand yearly for nearly seventy years. The source for the metal came from the rich silver mines of Siphnos, an island in the Aegean. Although Aegina was a formidable trading nation, the coins seemed to have meant for local use, as few have been found outside the Cyclades and Crete. So powerful was their lure, however, that an old proverb states, "Courage and wisdom are overcome by Turtles."

The Aeginean turtle bore a close likeness to that of its live counterpart, with a series of dots running down the center of its shell. The reverse of the coin bore the imprint of the punch used to force the face of the coin into the obverse turtle die. Originally this consisted of an eight-pronged punch that produced a pattern of eight triangles. Later, other variations on this were tried. In 480 BC, the coin received its first major redesign. Two extra pellets were added to the shell near the head of the turtle, a design not seen in nature. Also, the reverse punch mark was given a lopsided design.

Although turtles were produced in great quantities from 550 - 480 BC, after this time production dramatically declines. This may be due to the exhaustion of the silver mines on Siphnos, or it may be related to another historical event. In 480 BC, Aegina's archrival Athens defeated Xerxes and his Persian armies at Marathon. After this, it was Athens that became the predominant power in the region. Aegina and Athens fought a series of wars until 457 BC, when Aegina was conquered by its foe and stripped of its maritime rights. At this time the coin of Aegina changed its image from that of the sea turtle to that of the land tortoise, symbolizing its change in fortunes.

The Turtle was an object of desire in ancient times and has become so once again. It was the first coin produced in Europe, and was produced in such great quantities that thousands of Turtles still exist today. Their historical importance and ready availability make them one of the most desirable items in any ancient coin enthusiast's collection.

(Greek Turtles, by Gary T. Anderson .Cleisthenes

|

|

02. Persian Empire: Province of Cilicia: City of Tarsos.Double shekel, ca. 351 BC.

Obverse: Baal of Tarsos seated, holding eagle, ear of wheat, bunch of grapes, and sceptre.

Reverse: Lion attacking bull.

10.51 gm., 24 mm.

S. #5650; series V in Myriandros Katisson (E.T. Newell).Callimachus

|

|

020a, CARIA, Knidos. Circa 465-449 BC. AR Drachm.CARIA, Knidos. Circa 465-449 BC. AR Drachm - 16mm (6.06 g). Obverse: forepart of roaring lion right; Reverse: archaic head of Aphrodite right, hair bound with taenia. Cahn 80 (V38/R53); SNG Helsinki 132 (same dies); SNG Copenhagen 232 (same dies). Toned, near VF, good metal. Ex Barry P. Murphy.

While this coin falls within the time frame that numismatists call "Classical" Greek coinage, I have chosen to place it in both the "Archaic" (coin 020a) and "Classical" Greek sections of my collection. This specimen is one of those wonderful examples of transition--it incorporates many elements of the "Archaic" era, although it is struck during the "Classical" Greek period and anticipates characteristics of the later period.

As noted art historian Patricia Lawrence has pointed out, "[this specimen portrays] A noble-headed lion, a lovely Late Archaic Aphrodite, and [is made from]. . . beautiful metal." The Archaic Aphrodite is reminiscent of certain portraits of Arethusa found on tetradrachms produced in Syracuse in the first decade of the 5th century BC.

Knidos was a city of high antiquity and as a Hellenic city probably of Lacedaemonian colonization. Along with Halicarnassus (present day Bodrum, Turkey) and Kos, and the Rhodian cities of Lindos, Kamiros and Ialyssos it formed the Dorian Hexapolis, which held its confederate assemblies on the Triopian headland, and there celebrated games in honour of Apollo, Poseidon and the nymphs.

The city was at first governed by an oligarchic senate, composed of sixty members, and presided over by a magistrate; but, though it is proved by inscriptions that the old names continued to a very late period, the constitution underwent a popular transformation. The situation of the city was favourable for commerce, and the Knidians acquired considerable wealth, and were able to colonize the island of Lipara, and founded a city on Corcyra Nigra in the Adriatic. They ultimately submitted to Cyrus, and from the battle of Eurymedon to the latter part of the Peloponnesian War they were subject to Athens.

In their expansion into the region, the Romans easily obtained the allegiance of Knidians, and rewarded them for help given against Antiochus by leaving them the freedom of their city.

During the Byzantine period there must still have been a considerable population: for the ruins contain a large number of buildings belonging to the Byzantine style, and Christian sepulchres are common in the neighbourhood.

Eudoxus, the astronomer, Ctesias, the writer on Persian history, and Sostratus, the builder of the celebrated Pharos at Alexandria, are the most remarkable of the Knidians mentioned in history.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cnidus

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.Cleisthenes

|

|

028. Severus Alexander, 222-235. AR Denarius. Victoria.AR Denarius. Rome mint. AD 231-235.

Obv. Laureate head right IMP ALEXANDER PIVS AVG

Rev. Victoria standing left, left hand holding palm, right resting on shield, bound captive at feet VICTORIA AVG.

RIC 257, RSC 558a. aEF.

Struck to commemorate the 'victories' over the Persians in the emperors' eastern campaign of 231-233.LordBest

|

|

049a. MacrianusUsurper 260 - 261

Macrianus was the oldest son of Macrianus Senior (who was not viewed as a candidate for emperor due to his lameness and who did not strike coins). After Valerian was captured by the Sasanians, Macrianus tried to usurp the empire by naming his two sons, Macrianus Junior and Quietus as co-emperors in Summer 260. Macrianus Senior and Macrianus Junior succeeded in driving the Persians out of Antioch, but were defeated and killed in the Balkans in Summer 261 against Gallienus's troops.lawrence c

|

|

051 Caracalla (196-198 A.D. Caesar, 198-217 A.D. Augustus ), Rome, RIC IV-I 054b, AR-Denarius, PART MAX PONT TR P IIII, Trophy, #1051 Caracalla (196-198 A.D. Caesar, 198-217 A.D. Augustus ), Rome, RIC IV-I 054b, AR-Denarius, PART MAX PONT TR P IIII, Trophy, #1

avers: ANTONINVS PIVS AVG, Laureate, and draped bust right.

reverse: PART MAX PONT TR P IIII, Two Persians bound and seated back to back at the base of the trophy.

exergue: -/-//--, diameter: 18,0-19,0mm, weight: 3,00g, axis: 0h,

mint: Rome, date: 201 A.D.,

ref: RIC IV-I 054b, p-220, RSC 175cf, BMC 262, Sear 6853,

Q-001quadrans

|

|

070a. NumerianCaesar November/December 282 - February/March 283

Co-Augustus with brother Carinus and father Carus February/March 283 - July/August 283

Co-Augustus with brother Carinus July/August 283 - October/November 284

Numerian participated in the Persian campaign with his father, Carus. When Carus was killed, Numerian had to resolve the war and negotiated a peace with the Sasanids. On his return trip to the West, he was found dead in a closed litter. Arrius Aper was accused of the murder by Diocles, the head of the Emperor's bodyguard and was executed. It also has been argued that Diocles was in fact behind the murder. Diocles is better known by the name Diocletian, the future Augustus.lawrence c

|

|

091a. Constantius IICaesar 324-337. Emperor 337-361. Took control of the East. Off and on again wars with Persians. After Magnentius rose against Constans and had him killed, Constantius II beat him in 353 and controlled all the empire. Major persecution of pagans. Died of natural causes.lawrence c

|

|

097a. Julian II The ApostateAugustus 361-363.

Half-nephew of Constantine I. Somewhat accidently spared in the massacre of relatives by the sons of Constantine due to his youth. Caesar under Constantius II November 355-February 360. He rose up against Constantius in 360. Constantius moved forces to confront him, but Constantius died on the way. On his death bed, he named Julian as his successor. Julian tried to reinstate the pagan gods, but failed in his efforts. He was killed in wars with the Persians. Last of the Constantinian line.lawrence c

|

|

0a Amazon StaterSilver Stater 20mm Struck circa 440-410 B.C.

Soloi in Cilicia

Amazon kneeling left, holding bow, quiver on left hip

ΣOΛEΩN, Grape cluster on vine; A-Θ to either side of stalk, monogram to lower right

Sear 5602 var.; Casabonne Type 3; SNG France 135; SNG Levante

This coin depicts an amazon in historically accurate garb. Unfortunately, the bow is corroded away on this piece, but it is pointed toward her. She wears the Scythian hat, which also has a bit along the top corroded away. The quiver on her hip is an accurate portrayal of the gorytos (quiver), which was nearly two feet long, fashioned of leather, and often decorated. Fortunately, there is redundancy in this image, and a second bow is shown as in its place in the gorytos, which had separate chambers for arrows and the bow, where the archer stored it while not in use. The amazon has just finished stringing her bow and is adjusting the top hook to make sure the strings and limbs are properly aligned. She has strung the bow using her leg to hold one limb in place so she can use both hands to string the weapon. Her recurve bow was made of horn (ibex, elk, ox) wrapped with horse hair, birch bark, or sinew (deer, elk, ox) and glue (animal or fish) wrapped around a wood core. The bow was about 30 inches long. Arrow heads from grave sites come in bone, wood, iron, and bronze with two or three flanges; the shafts were made of reed or wood (willow, birch, poplar) and fletched with feathers. Poisoned arrows were sometimes painted to resemble vipers. A Scythian archer could probably fire 15-20 arrows per minute with accuracy to 200 feet and range to 500-600 feet. Distance archery with modern reconstructions suggests a maximum unaimed flight distance of 1,600 feet. (Mayor 209ff)

Soloi was founded about 700 B.C.and came under Persian rule. According to Diodorus, when the amazons were engaging in conquest in Asia Minor, the Cilicians accepted them willingly and retained their independence. Soloi may be named after Solois, a companion of Theseus, who married the amazon Antiope. The amazon on the coin may well be Antiope. (Mayor, 264-265)Blindado

|

|

1.0 Khusroe IIKhusroe II

Sassanian (Persian) Empire

Silver Dirhem

30 mm.

Khusroe II conquered Jerusalem from the Byzantine Empire, but soon lost it in a counter offensive by Emperor Heraclius.Ecgþeow

|

|

1301a, Diocletian, 284-305 A.D. (Antioch)DIOCLETIAN (284 – 305 AD) AE Antoninianus, 293-95 AD, RIC V 322, Cohen 34. 20.70 mm/3.1 gm, aVF, Antioch. Obverse: IMP C C VAL DIOCLETIANVS P F AVG, Radiate bust right, draped & cuirassed; Reverse: CONCORDIA MILITVM, Jupiter presents Victory on a globe to Diocletian, I/XXI. Early Diocletian with dusty earthen green patina.

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Diocletian ( 284-305 A.D.)

Ralph W. Mathisen

University of South Carolina

Summary and Introduction

The Emperor Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus (A.D. 284-305) put an end to the disastrous phase of Roman history known as the "Military Anarchy" or the "Imperial Crisis" (235-284). He established an obvious military despotism and was responsible for laying the groundwork for the second phase of the Roman Empire, which is known variously as the "Dominate," the "Tetrarchy," the "Later Roman Empire," or the "Byzantine Empire." His reforms ensured the continuity of the Roman Empire in the east for more than a thousand years.

Diocletian's Early Life and Reign

Diocletian was born ca. 236/237 on the Dalmatian coast, perhaps at Salona. He was of very humble birth, and was originally named Diocles. He would have received little education beyond an elementary literacy and he was apparently deeply imbued with religious piety He had a wife Prisca and a daughter Valeria, both of whom reputedly were Christians. During Diocletian's early life, the Roman empire was in the midst of turmoil. In the early years of the third century, emperors increasingly insecure on their thrones had granted inflationary pay raises to the soldiers. The only meaningful income the soldiers now received was in the form of gold donatives granted by newly acclaimed emperors. Beginning in 235, armies throughout the empire began to set up their generals as rival emperors. The resultant civil wars opened up the empire to invasion in both the north, by the Franks, Alamanni, and Goths, and the east, by the Sassanid Persians. Another reason for the unrest in the army was the great gap between the social background of the common soldiers and the officer corps.

Diocletian sought his fortune in the army. He showed himself to be a shrewd, able, and ambitious individual. He is first attested as "Duke of Moesia" (an area on the banks of the lower Danube River), with responsibility for border defense. He was a prudent and methodical officer, a seeker of victory rather than glory. In 282, the legions of the upper Danube proclaimed the praetorian prefect Carus as emperor. Diocletian found favor under the new emperor, and was promoted to Count of the Domestics, the commander of the cavalry arm of the imperial bodyguard. In 283 he was granted the honor of a consulate.

In 284, in the midst of a campaign against the Persians, Carus was killed, struck by a bolt of lightning which one writer noted might have been forged in a legionary armory. This left the empire in the hands of his two young sons, Numerian in the east and Carinus in the west. Soon thereafter, Numerian died under mysterious circumstances near Nicomedia, and Diocletian was acclaimed emperor in his place. At this time he changed his name from Diocles to Diocletian. In 285 Carinus was killed in a battle near Belgrade, and Diocletian gained control of the entire empire.

Diocletian's Administrative and Military Reforms

As emperor, Diocletian was faced with many problems. His most immediate concerns were to bring the mutinous and increasingly barbarized Roman armies back under control and to make the frontiers once again secure from invasion. His long-term goals were to restore effective government and economic prosperity to the empire. Diocletian concluded that stern measures were necessary if these problems were to be solved. He felt that it was the responsibility of the imperial government to take whatever steps were necessary, no matter how harsh or innovative, to bring the empire back under control.

Diocletian was able to bring the army back under control by making several changes. He subdivided the roughly fifty existing provinces into approximately one hundred. The provinces also were apportioned among twelve "dioceses," each under a "vicar," and later also among four "prefectures," each under a "praetorian prefect." As a result, the imperial bureaucracy became increasingly bloated. He institutionalized the policy of separating civil and military careers. He divided the army itself into so-called "border troops," actually an ineffective citizen militia, and "palace troops," the real field army, which often was led by the emperor in person.

Following the precedent of Aurelian (A.D.270-275), Diocletian transformed the emperorship into an out-and-out oriental monarchy. Access to him became restricted; he now was addressed not as First Citizen (Princeps) or the soldierly general (Imperator), but as Lord and Master (Dominus Noster) . Those in audience were required to prostrate themselves on the ground before him.

Diocletian also concluded that the empire was too large and complex to be ruled by only a single emperor. Therefore, in order to provide an imperial presence throughout the empire, he introduced the "Tetrarchy," or "Rule by Four." In 285, he named his lieutenant Maximianus "Caesar," and assigned him the western half of the empire. This practice began the process which would culminate with the de facto split of the empire in 395. Both Diocletian and Maximianus adopted divine attributes. Diocletian was identified with Jupiter and Maximianus with Hercules. In 286, Diocletian promoted Maximianus to the rank of Augustus, "Senior Emperor," and in 293 he appointed two new Caesars, Constantius (the father of Constantine I ), who was given Gaul and Britain in the west, and Galerius, who was assigned the Balkans in the east.

By instituting his Tetrarchy, Diocletian also hoped to solve another problem. In the Augustan Principate, there had been no constitutional method for choosing new emperors. According to Diocletian's plan, the successor of each Augustus would be the respective Caesar, who then would name a new Caesar. Initially, the Tetrarchy operated smoothly and effectively.

Once the army was under control, Diocletian could turn his attention to other problems. The borders were restored and strengthened. In the early years of his reign, Diocletian and his subordinates were able to defeat foreign enemies such as Alamanni, Sarmatians, Saracens, Franks, and Persians, and to put down rebellions in Britain and Egypt. The easter frontier was actually expanded.

.

Diocletian's Economic Reforms

Another problem was the economy, which was in an especially sorry state. The coinage had become so debased as to be virtually worthless. Diocletian's attempt to reissue good gold and silver coins failed because there simply was not enough gold and silver available to restore confidence in the currency. A "Maximum Price Edict" issued in 301, intended to curb inflation, served only to drive goods onto the black market. Diocletian finally accepted the ruin of the money economy and revised the tax system so that it was based on payments in kind . The soldiers too came to be paid in kind.

In order to assure the long term survival of the empire, Diocletian identified certain occupations which he felt would have to be performed. These were known as the "compulsory services." They included such occupations as soldiers, bakers, members of town councils, and tenant farmers. These functions became hereditary, and those engaging in them were inhibited from changing their careers. The repetitious nature of these laws, however, suggests that they were not widely obeyed. Diocletian also expanded the policy of third-century emperors of restricting the entry of senators into high-ranking governmental posts, especially military ones.

Diocletian attempted to use the state religion as a unifying element. Encouraged by the Caesar Galerius, Diocletian in 303 issued a series of four increasingly harsh decrees designed to compel Christians to take part in the imperial cult, the traditional means by which allegiance was pledged to the empire. This began the so-called "Great Persecution."

Diocletian's Resignation and Death

On 1 May 305, wearied by his twenty years in office, and determined to implement his method for the imperial succession, Diocletian abdicated. He compelled his co-regent Maximianus to do the same. Constantius and Galerius then became the new Augusti, and two new Caesars were selected, Maximinus (305-313) in the east and Severus (305- 307) in the west. Diocletian then retired to his palace at Split on the Croatian coast. In 308 he declined an offer to resume the purple, and the aged ex-emperor died at Split on 3 December 316.

Copyright (C) 1996, Ralph W. Mathisen, University of South Carolina

Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

1301b, Diocletian, 20 November 284 - 1 March 305 A.D.Diocletian. RIC V Part II Cyzicus 256 var. Not listed with pellet in exegrue

Item ref: RI141f. VF. Minted in Cyzicus (B in centre field, XXI dot in exegrue)Obverse:- IMP CC VAL DIOCLETIANVS AVG, Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right. Reverse:- CONCORDIA MILITVM, Diocletian standing right, holding parazonium, receiving Victory from Jupiter standing left with scepter.

A post reform radiate of Diocletian. Ex Maridvnvm.

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Diocletian ( 284-305 A.D.)

Ralph W. Mathisen

University of South Carolina

Summary and Introduction

The Emperor Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus (A.D. 284-305) put an end to the disastrous phase of Roman history known as the "Military Anarchy" or the "Imperial Crisis" (235-284). He established an obvious military despotism and was responsible for laying the groundwork for the second phase of the Roman Empire, which is known variously as the "Dominate," the "Tetrarchy," the "Later Roman Empire," or the "Byzantine Empire." His reforms ensured the continuity of the Roman Empire in the east for more than a thousand years.

Diocletian's Early Life and Reign

Diocletian was born ca. 236/237 on the Dalmatian coast, perhaps at Salona. He was of very humble birth, and was originally named Diocles. He would have received little education beyond an elementary literacy and he was apparently deeply imbued with religious piety He had a wife Prisca and a daughter Valeria, both of whom reputedly were Christians. During Diocletian's early life, the Roman empire was in the midst of turmoil. In the early years of the third century, emperors increasingly insecure on their thrones had granted inflationary pay raises to the soldiers. The only meaningful income the soldiers now received was in the form of gold donatives granted by newly acclaimed emperors. Beginning in 235, armies throughout the empire began to set up their generals as rival emperors. The resultant civil wars opened up the empire to invasion in both the north, by the Franks, Alamanni, and Goths, and the east, by the Sassanid Persians. Another reason for the unrest in the army was the great gap between the social background of the common soldiers and the officer corps.

Diocletian sought his fortune in the army. He showed himself to be a shrewd, able, and ambitious individual. He is first attested as "Duke of Moesia" (an area on the banks of the lower Danube River), with responsibility for border defense. He was a prudent and methodical officer, a seeker of victory rather than glory. In 282, the legions of the upper Danube proclaimed the praetorian prefect Carus as emperor. Diocletian found favor under the new emperor, and was promoted to Count of the Domestics, the commander of the cavalry arm of the imperial bodyguard. In 283 he was granted the honor of a consulate.

In 284, in the midst of a campaign against the Persians, Carus was killed, struck by a bolt of lightning which one writer noted might have been forged in a legionary armory. This left the empire in the hands of his two young sons, Numerian in the east and Carinus in the west. Soon thereafter, Numerian died under mysterious circumstances near Nicomedia, and Diocletian was acclaimed emperor in his place. At this time he changed his name from Diocles to Diocletian. In 285 Carinus was killed in a battle near Belgrade, and Diocletian gained control of the entire empire.

Diocletian's Administrative and Military Reforms

As emperor, Diocletian was faced with many problems. His most immediate concerns were to bring the mutinous and increasingly barbarized Roman armies back under control and to make the frontiers once again secure from invasion. His long-term goals were to restore effective government and economic prosperity to the empire. Diocletian concluded that stern measures were necessary if these problems were to be solved. He felt that it was the responsibility of the imperial government to take whatever steps were necessary, no matter how harsh or innovative, to bring the empire back under control.

Diocletian was able to bring the army back under control by making several changes. He subdivided the roughly fifty existing provinces into approximately one hundred. The provinces also were apportioned among twelve "dioceses," each under a "vicar," and later also among four "prefectures," each under a "praetorian prefect." As a result, the imperial bureaucracy became increasingly bloated. He institutionalized the policy of separating civil and military careers. He divided the army itself into so-called "border troops," actually an ineffective citizen militia, and "palace troops," the real field army, which often was led by the emperor in person.

Following the precedent of Aurelian (A.D.270-275), Diocletian transformed the emperorship into an out-and-out oriental monarchy. Access to him became restricted; he now was addressed not as First Citizen (Princeps) or the soldierly general (Imperator), but as Lord and Master (Dominus Noster) . Those in audience were required to prostrate themselves on the ground before him.

Diocletian also concluded that the empire was too large and complex to be ruled by only a single emperor. Therefore, in order to provide an imperial presence throughout the empire, he introduced the "Tetrarchy," or "Rule by Four." In 285, he named his lieutenant Maximianus "Caesar," and assigned him the western half of the empire. This practice began the process which would culminate with the de facto split of the empire in 395. Both Diocletian and Maximianus adopted divine attributes. Diocletian was identified with Jupiter and Maximianus with Hercules. In 286, Diocletian promoted Maximianus to the rank of Augustus, "Senior Emperor," and in 293 he appointed two new Caesars, Constantius (the father of Constantine I ), who was given Gaul and Britain in the west, and Galerius, who was assigned the Balkans in the east.

By instituting his Tetrarchy, Diocletian also hoped to solve another problem. In the Augustan Principate, there had been no constitutional method for choosing new emperors. According to Diocletian's plan, the successor of each Augustus would be the respective Caesar, who then would name a new Caesar. Initially, the Tetrarchy operated smoothly and effectively.

Once the army was under control, Diocletian could turn his attention to other problems. The borders were restored and strengthened. In the early years of his reign, Diocletian and his subordinates were able to defeat foreign enemies such as Alamanni, Sarmatians, Saracens, Franks, and Persians, and to put down rebellions in Britain and Egypt. The easter frontier was actually expanded.

.

Diocletian's Economic Reforms

Another problem was the economy, which was in an especially sorry state. The coinage had become so debased as to be virtually worthless. Diocletian's attempt to reissue good gold and silver coins failed because there simply was not enough gold and silver available to restore confidence in the currency. A "Maximum Price Edict" issued in 301, intended to curb inflation, served only to drive goods onto the black market. Diocletian finally accepted the ruin of the money economy and revised the tax system so that it was based on payments in kind . The soldiers too came to be paid in kind.

In order to assure the long term survival of the empire, Diocletian identified certain occupations which he felt would have to be performed. These were known as the "compulsory services." They included such occupations as soldiers, bakers, members of town councils, and tenant farmers. These functions became hereditary, and those engaging in them were inhibited from changing their careers. The repetitious nature of these laws, however, suggests that they were not widely obeyed. Diocletian also expanded the policy of third-century emperors of restricting the entry of senators into high-ranking governmental posts, especially military ones.

Diocletian attempted to use the state religion as a unifying element. Encouraged by the Caesar Galerius, Diocletian in 303 issued a series of four increasingly harsh decrees designed to compel Christians to take part in the imperial cult, the traditional means by which allegiance was pledged to the empire. This began the so-called "Great Persecution."

Diocletian's Resignation and Death

On 1 May 305, wearied by his twenty years in office, and determined to implement his method for the imperial succession, Diocletian abdicated. He compelled his co-regent Maximianus to do the same. Constantius and Galerius then became the new Augusti, and two new Caesars were selected, Maximinus (305-313) in the east and Severus (305- 307) in the west. Diocletian then retired to his palace at Split on the Croatian coast. In 308 he declined an offer to resume the purple, and the aged ex-emperor died at Split on 3 December 316.

Copyright (C) 1996, Ralph W. Mathisen, University of South Carolina

Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

1303a, Galerius, 1 March 305 - 5 May 311 A.D.Galerius, RIC VI 59, Cyzicus S, VF, Cyzicus S, 6.4 g, 25.86 mm; 309-310 AD; Obverse: GAL MAXIMIANVS P F AVG, laureate bust right; Reverse: GENIO A-VGVS[TI], Genius stg. left, naked but for chlamys over left shoulder, holding patera and cornucopiae. A nice example with sharp detail and nice brown hoard patina. Ex Ancient Imports.

De Imperatoribus Romanis,

An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors

Galerius (305-311 A.D.)

Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Salve Regina University

Caius Galerius Valerius Maximianus, more commonly known as Galerius, was from Illyricum; his father, whose name is unknown, was of peasant stock, while his mother, Romula, was from beyond the Danube. Galerius was born in Dacia Ripensis near Sardica. Although the date of his birth is unknown, he was probably born ca. 250 since he served under Aurelian. As a youth Galerius was a shepherd and acquired the nickname Armentarius. Although he seems to have started his military career under Aurelian and Probus, nothing is known about it before his accession as Caesar on 1 March 293. He served as Diocletian's Caesar in the East. Abandoning his first wife, he married Diocletian's daugher, Valeria.

As Caesar he campaigned in Egypt in 294; he seems to have taken to the field against Narses of Persia, and was defeated near Ctesiphon in 295. In 298, after he made inroads into Armenia, he obtained a treaty from the Persians favorable to the Romans. Between 299-305 he overcame the Sarmatians and the Carpi along the Danube. The Great Persecution of the Orthodox Church, which was started in 303 by the Emperor Diocletian, was probably instigated by Galerius. Because of the almost fatal illness that he contracted toward the end of 304, Diocletian, at Nicomedeia, and Maximianus Herculius, at Mediolanum, divested themselves of the purple on 1 May 305. Constantius and Galerius were appointed as Augusti, with Maximinus Daia and Severus as the new Caesars. Constantius and Severus reigned in the West, whereas Galerius' and Daia's realm was the East. Although Constantius was nominally senior Augustus, the real power was in the hands of Galerius because both Caesars were his creatures.

The balance of power shifted at the end of July 306 when Constantius, with his son Constantine at his side, passed away at York in Britain where he was preparing to face incursions by the Picts; his army proclaimed Constantine his successor immediately. As soon as he received the news of the death of Constantius I and the acclamation of Constantine to the purple, Galerius raised Severus to the rank of Augustus to replace his dead colleague in August 306. Making the best of a bad situation, Galerius accepted Constantine as the new Caesar in the West. The situation became more complicated when Maxentius, with his father Maximianus Herculius acquiesing, declared himself princes on 28 October 306. When Galerius learned about the acclamation of the usurper, he dispatched the Emperor Severus to put down the rebellion. Severus took a large field army which had formerly been that of Maximianus and proceeded toward Rome and began to besiege the city, Maxentius, however, and Maximianus, by means of a ruse, convinced Severus to surrender. Later, in 307, Severus was put to death under clouded circumstances. While Severus was fighting in the west, Galerius, during late 306 or early 307, was campaigning against the Sarmatians.

In the early summer of 307 Galerius invaded Italy to avenge Severus's death; he advanced to the south and encamped at Interamna near the Tiber. His attempt to besiege the city was abortive because his army was too small to encompass the city's fortifications. Not trusting his own troops, Galerius withdrew. During its retreat, his army ravaged the Italian countryside as it was returning to its original base. When Maximianus Herculius' attempts to regain the throne between 308 and 310 by pushing his son off his throne or by winning over Constantine to his cause failed, he tried to win Diocletian and Galerius over to his side at Carnuntum in October and November 308; the outcome of the Conference at Carnuntum was that Licinius was appointed Augustus in Severus's place, that Daia and Constantine were denoted filii Augustorum, and that Herculius was completely cut out of the picture. Later, in 310, Herculius died, having been implicated in a plot against his son-in-law. After the Conference at Carnuntum, Galerius returned to Sardica where he died in the opening days of May 311.

By Michael DiMaio, Jr., Salve Regina University; Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Galerius was Caesar and tetrarch under Maximianus. Although a talented general and administrator, Galerius is better known for his key role in the "Great Persecution" of Christians. He stopped the persecution under condition the Christians pray for his return to health from a serious illness. Galerius died horribly shortly after. Joseph Sermarini, FORVM.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

1308b, Licinius I, 308 - 324 A.D. (Siscia)Licinius I, 11 November 308 - 18 September 324 A.D. Bronze follis, RIC 4, F, Siscia, 3.257g, 21.6mm, 0o, 313 - 315 A.D. Obverse: IMP LIC LICINIVS P F AVG, laureate head right; Reverse IOVI CONSERVATORI AVGG NN, Jupiter standing left holding Victory on globe and scepter, eagle with wreath in beak left, E right, SIS in exergue.

De Imperatoribus Romanis : An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Licinius (308-324 A.D.)

Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Salve Regina University

Licinius' Heritage

Valerius Licinianus Licinius, more commonly known as Licinius, may have been born ca. 265. Of peasant origin, his family was from Dacia. A close friend and comrade of arms of the Emperor Galerius, he accompanied him on his Persian expedition in 297. When campaigns by Severus and Galerius in late 306 or early 307 and in the summer of 307, respectively, failed to dislodge Maxentius who, with the luke warm support of his father Maximianus Herculius, was acclaimed princeps on 28 October 306, he was sent by the eastern emperor to Maxentius as an ambassador; the diplomatic mission, however, failed because the usurper refused to submit to the authority of his father-in-law Galerius. At the Conference of Carnuntum which was held in October or November of 308, Licinius was made an Augustus on 11 November 308; his realm included Thrace, Illyricum, and Pannonia.

Licinius' Early Reign

Although Licinius was initially appointed by Galerius to replace Severus to end the revolt of Maxentius , Licinius (perhaps wisely) made no effort to move against the usurper. In fact, his first attested victory was against the Sarmatians probably in the late spring, but no later than the end of June in 310. When the Emperor Galerius died in 311, Licinius met Maximinus Daia at the Bosporus during the early summer of that year; they concluded a treaty and divided Galerius' realm between them. It was little more than a year later that the Emperor Constantine defeated Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge on 28 October 312. After the defeat of the usurper, Constantine and Licinius met at Mediolanum (Milan) where Licinius married the former's sister Constantia; one child was born of this union: Valerius Licinianus Licinius. Licinius had another son, born of a slave woman, whose name is unknown. It appears that both emperors promulgated the so-called Edict of Milan, in which Constantine and Licinius granted Christians the freedom to practice their faith without any interference from the state.

As soon as he seems to have learned about the marital alliance between Licinius and Constantine and the death of Maxentius, who had been his ally, Daia traversed Asia Minor and, in April 313, he crossed the Bosporus and went to Byzantium, which he took from Licinius after an eleven day siege. On 30 April 313 the armies of both emperors clashed on the Campus Ergenus; in the ensuing battle Daia's forces were routed. A last ditch stand by Daia at the Cilician Gates failed; the eastern emperor subsequently died in the area of Tarsus probably in July or August 313. As soon as he arrived in Nicomedeia, Licinius promulgated the Edict of Milan. As soon as he had matters in Nicomedeia straightened out, Licinius campaigned against the Persians in the remaining part of 313 and the opening months of 314.

The First Civil War Between Licinius and Constantine

Once Licinius had defeated Maximinus Daia, the sole rulers of the Roman world were he and Constantine. It is obvious that the marriage of Licinius to Constantia was simply a union of convenience. In any case, there is evidence in the sources that both emperors were looking for an excuse to attack the other. The affair involving Bassianus (the husband of Constantius I's daughter Anastasia ), mentioned in the text of Anonymus Valesianus (5.14ff), may have sparked the falling out between the two emperors. In any case, Constantine' s forces joined battle with those of Licinius at Cibalae in Pannonia on 8 October 314. When the battle was over, Constantine prevailed; his victory, however, was Pyrrhic. Both emperors had been involved in exhausting military campaigns in the previous year and the months leading up to Cibalae and each of their realms had expanded so fast that their manpower reserves must have been stretched to the limit. Both men retreated to their own territory to lick their wounds. It may well be that the two emperors made an agreement, which has left no direct trace in the historical record, which would effectively restore the status quo.

Both emperors were variously engaged in different activities between 315 and 316. In addition to campaigning against the Germans while residing in Augusta Treverorum (Trier) in 315, Constantine dealt with aspects of the Donatist controversy; he also traveled to Rome where he celebrated his Decennalia. Licinius, possibly residing at Sirmium, was probably waging war against the Goths. Although not much else is known about Licinius' activities during this period, it is probable that he spent much of his time preparing for his impending war against Constantine; the latter,who spent the spring and summer of 316 in Augusta Treverorum, was probably doing much the same thing. In any case, by December 316, the western emperor was in Sardica with his army. Sometime between 1 December and 28 February 317, both emperors' armies joined battle on the Campus Ardiensis; as was the case in the previous engagement, Constantine' s forces were victorious. On 1 March 317, both sides agreed to a cessation of hostilities; possibly because of the intervention of his wife Constantia, Licinius was able to keep his throne, although he had to agree to the execution of his colleague Valens, who the eastern emperor had appointed as his colleague before the battle, as well as to cede some of his territory to his brother-in-law.

Licinius and the Christians

Although the historical record is not completely clear, Licinius seems to have campaigned against the Sarmatians in 318. He also appears to have been in Byzantium in the summer of 318 and later in June 323. Beyond these few facts, not much else is known about his residences until mid summer of 324. Although he and Constantine had issued the Edict of Milan in early 313, Licinius turned on the Christians in his realm seemingly in 320. The first law that Licinius issued prevented bishops from communicating with each other and from holding synods to discuss matters of interest to them. The second law prohibited men and women from attending services together and young girls from receiving instruction from their bishop or schools. When this law was issued, he also gave orders that Christians could hold services only outside of city walls. Additionally, he deprived officers in the army of their commissions if they did not sacrifice to the gods. Licinius may have been trying to incite Constantine to attack him. In any case, the growing tension between the two rulers is reflected in the consular Fasti of the period.

The Second Civil War Between Licinius and Constantine and Licinius' Death

War actually broke out in 321 when Constantine pursued some Sarmatians, who had been ravaging some territory in his realm, across the Danube. When he checked a similar invasion of the Goths, who were devastating Thrace, Licinius complained that Constantine had broken the treaty between them. Having assembled a fleet and army at Thessalonica, Constantine advanced toward Adrianople. Licinius engaged the forces of his brother-in-law near the banks of the Hebrus River on 3 July 324 where he was routed; with as many men as he could gather, he headed for his fleet which was in the Hellespont. Those of his soldiers who were not killed or put to flight, surrendered to the enemy. Licinius fled to Byzantium, where he was besieged by Constantine. Licinius' fleet, under the command of the admiral Abantus, was overcome by bad weather and by Constantine' s fleet which was under the command of his son Crispus. Hard pressed in Byzantium, Licinius abandoned the city to his rival and fled to Chalcedon in Bithynia. Leaving Martinianus, his former magister officiorum and now his co-ruler, to impede Constantine' s progress, Licinius regrouped his forces and engaged his enemy at Chrysopolis where he was again routed on 18 September 324. He fled to Nicomedeia which Constantine began to besiege. On the next day Licinius abdicated and was sent to Thessalonica, where he was kept under house arrest. Both Licinius and his associate were put to death by Constantine. Martinianus may have been put to death before the end of 324, whereas Licinius was not put to death until the spring of 325. Rumors circulated that Licinius had been put to death because he attempted another rebellion against Constantine.

Copyright (C) 1996, Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Published: De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families http://www.roman-emperors.org/startup.htm. Used by permission.

Edited by J. P. Fitzgerald, Jr.

Cleisthenes

|

|

1308c, Licinius I, 308-324 A.D. (Alexandria)Licinius I, 308-324 A.D. AE Follis, 3.60g, VF, 315 A.D., Alexandria. Obverse: IMP C VAL LICIN LICINIVS P F AVG - Laureate head right; Reverse: IOVI CONS-ERVATORI AVGG - Jupiter standing left, holding Victory on a globe and scepter; exergue: ALE / (wreath) over "B" over "N." Ref: RIC VII, 10 (B = r2) Rare, page 705 - Hunterian Museum, Glasgow, Scotland.

De Imperatoribus Romanis : An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families

Licinius (308-324 A.D.)

Michael DiMaio, Jr.